Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:02 — 23.0MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Speculators are responsible for food price spikes? Food price spikes are responsible for riots in the streets? First-world hipsters are responsible for hungry quinoa farmers in Peru?

No, yes, no – at least if you care more about evidence than emotions and opinions.

How do we know? Thanks to the work of agricultural economists like my guest in this episode, Marc Bellemare, director of the Center for International Food and Agricultural Policy at the University of Minnesota. I confess, I’m a little in awe of the analytical skills of ag-economists, their ability to find datasets and then persuade them to offer up reasonable answers. Sometimes it seems emotion and opinion are much easier ways to interpret the world, but I’m glad there are people who disagree. Marc was in Rome recently, and allowed me some time to talk about economics and agriculture.

Notes

- Marc Bellemare has a blog, and he’s not afraid to use it.

- Previous episodes: the one about price spikes and the one about quinoa.

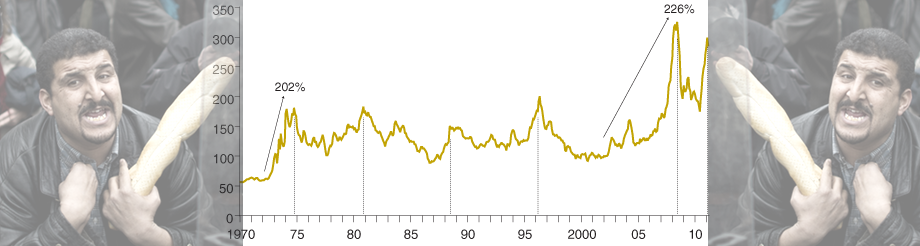

- The graph in the banner photograph is from a rather good article from the USDA: Why Another Food Commodity Price Spike?

People accused me of being a tease when I originally published that banner photograph up there and said that it was not a zucchini. It was, I admit, a deliberate provocation. It all depends on whether we’re speaking English or Italian. Because in English it isn’t, strictly speaking, a zucchini. It is a cocozelle, a type of summer squash that differs from a zucchini in a couple of important ways, one being that it hangs onto its flower a lot longer. So a flower on a cocozelle is not the guarantee of freshness that it is on a true zucchini. In Italian, however, it is a zucchini. Or rather, a zucchina. Because in modern Italian, all summer squashes are zucchine.

People accused me of being a tease when I originally published that banner photograph up there and said that it was not a zucchini. It was, I admit, a deliberate provocation. It all depends on whether we’re speaking English or Italian. Because in English it isn’t, strictly speaking, a zucchini. It is a cocozelle, a type of summer squash that differs from a zucchini in a couple of important ways, one being that it hangs onto its flower a lot longer. So a flower on a cocozelle is not the guarantee of freshness that it is on a true zucchini. In Italian, however, it is a zucchini. Or rather, a zucchina. Because in modern Italian, all summer squashes are zucchine.