Following up on the cost of a nutritious diet, a couple of studies: obese people have different spending patterns, and whether subsidised community supported agriculture improves quality of diet.

I think it was Professor David Zilberman of UC Berkeley and his colleagues who first coined the phrase Fat taxes, thin subsidies in a 2004 paper that calculated the potential health benefits of subsidies on certain classes of fruits and vegetables. Those calculations showed that “[e]stimates of the cost per statistical life saved through such subsidies compare favorably with existing U.S. government programs.” The phrase now crops up on both sides of the debate.

The latest meta-analysis, for example, says thin subsidies and fat taxes both do what they’re intended to do, increase the consumption of healthy foods and decrease the consumption of unhealthy foods.

Nevertheless, some say that fat taxes and thin subsidies remain a bad idea because they favour wealthier consumers. Rich people already buy healthier food, so thin subsidies just reduce their food bill. Furthermore, rich people wouldn’t contribute much to the fat tax. Poorer people are buying unhealthy food, so increasing their costs with fat taxes does them no good unless they also change their purchasing habits. One way to do that, of course, is to provide education about nutrition, and there’s a prevalent view that some of the fat tax revenue could be used to provide that education. It seems a bit rum, though, to expect the poor to finance their own education through the fat tax.

Anyway, most of the research to date has looked at how poorer and richer people would respond to these various economic incentives. What if the differences in how people buy food depend more on whether they are obese or normal weight than whether they are poor or rich?

Rich fat Russians

In Russia, at least, it does. Matthias Staudigel, of the Institute of Agricultural Policy and Market Research at the University of Giessen in Germany asked How do obese people afford to be obese? Consumption strategies of Russian households in a paper published in 2012. Russia is a good place to ask the question for a couple of reaons. First, the economy fluctuated fairly wildly during the transition and through the rouble crisis of 1998. Secondly, the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey combines detailed economic data with measures of height and weight for household members. So there are good measures of what household members weigh and how they spend on food under varying economic conditions.

In principle, consumers could respond to higher prices (or lower incomes) in three broad ways. They could allocate a different part of their spending to food, they could buy different amounts of specific foods and they could buy foods of different quality.

Faced with higher prices, obese households (but not those who are merely overweight or normal) tend to buy the same amount of food, but of lower quality. Differences in the amount they spend and in the amount they buy are lower or non existent. Faced with a fat tax, obese consumers (in Russia) would probably just shift to cheaper versions of the same foods. As Staudigel concludes, “policies aiming to reduce obesity should consider deviations in consumption behavior of normal and obese consumers in terms of quality”.

Poor obese Americans

In Russia, obese households are richer than overweight and normal households. They spend more in total and on food. In the US, the reverse is true. Obesity and overweight is associated more with poverty.

In the US, households headed by an obese person have a different spending pattern than those headed by an overweight or normal weight person. They spend more, percentage wise, on cheese, processed meat and meat, poultry and seafood and less on fruit, vegetables, juice, milk and yogurt and cereal and snacks. Obese shoppers allocate most of their additional spending to processed meals, processed meat and sweets. To compensate, they allocate less to fruits and vegetables.

Shoppers also differ in how they respond to price changes. In general, obese shoppers are less responsive to price changes than overweight and normal shoppers. So fat taxes, at least on the things obese shoppers buy, are not going to change their behaviour as much as might be expected.

Get real

Against the theoretical models of the economists, it’s nice to come across news of a study that plans to look at how people will respond IRL to at least one thin subsidy. The study is called Community Supported Agriculture Cost-offset Intervention to Prevent Childhood Obesity and Strengthen Local Agricultural Economies, which despite being a giant mouthful says exactly what they plan to do.

Community supported agriculture (CSA) takes many forms, but essentially participants pay a farmer upfront for a season’s worth of vegetables and fruit. The farmers get a financial guarantee and some stability, and the community gets fruit and vegetables at significantly lower cost. For a variety of reasons – such as the upfront cost of a share, inconvenient pick-up points and not knowing what to do with some of the produce – poorer communities are less likely to take part in CSA schemes, even though they probably have most to gain.

Subsidised CSA schemes could offer several benefits: better quality diets for poor people, reduced obesity, especially for children, and support for thriving local agriculture. All of that is yet to come; the article describes the initial research to design the study and how exactly they are going to encourage poorer families to participate and make use of the produce they find in their CSA boxes. It is worth bookmarking now as a repository of evidence on the many linkages among CSAs, fruits and vegetables, economics and health.

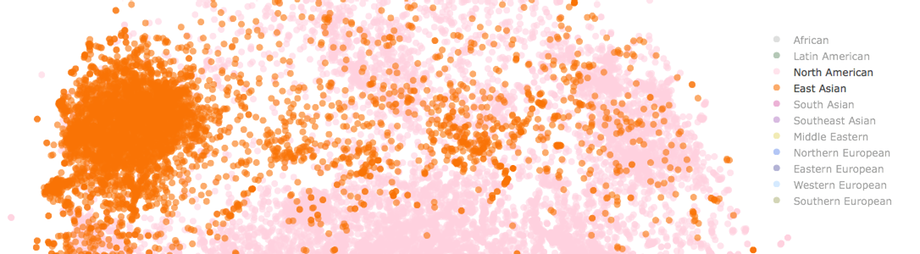

Recommendation engines are everywhere. They let Netflix suggest shows you might want to watch. They let Spotify build you a personalised playlist of music you will probably like. They turn your smartphone into a source of endless hilarity and mirth. And, of course, there’s IBM’s Watson, recommending all sorts of “interesting” new recipes. As part of his PhD project on machine learning, Jaan Altosaar decided to use a new mathematical technique to build his own recipe recommendation engine.

Recommendation engines are everywhere. They let Netflix suggest shows you might want to watch. They let Spotify build you a personalised playlist of music you will probably like. They turn your smartphone into a source of endless hilarity and mirth. And, of course, there’s IBM’s Watson, recommending all sorts of “interesting” new recipes. As part of his PhD project on machine learning, Jaan Altosaar decided to use a new mathematical technique to build his own recipe recommendation engine.

Last night I was lucky enough to go to

Last night I was lucky enough to go to

Recently I’ve been involved in a couple of online discussions about the cost of a nutritious diet. The crucial issue is why poor people in rich countries seem to have such unhealthy diets. One argument is about the cost of food. Another is about everything other than cost: knowledge, equipment, time, conditions.

Recently I’ve been involved in a couple of online discussions about the cost of a nutritious diet. The crucial issue is why poor people in rich countries seem to have such unhealthy diets. One argument is about the cost of food. Another is about everything other than cost: knowledge, equipment, time, conditions.