Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:47 — 19.3MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Who invented mayonnaise? Could boiling down tonnes of cattle concentrate beef’s nutritious qualities? Did lemonade put a halt to the plague in Paris?

Who invented mayonnaise? Could boiling down tonnes of cattle concentrate beef’s nutritious qualities? Did lemonade put a halt to the plague in Paris?

Tom Nealon writes about these and (many) other topics in his book Food Fights and Culture Wars, a title that does the contents no favours at all. The obvious temptation is to talk about the book as a feast of food history, a smörgåsbord of tasty treats, some old, some new, all interesting. It is all that and more, not least because it is lavishly illustrated with fascinating images. All in all, a great read, but a hard topic for an episode, because the only thing that really connects all those dots is Tom Nealon himself. We talked a lot, covered a lot of ground and, inevitably, left a lot of things out.

I think I disagree with Tom on at least one thing: cannibalism. I’m just not as persuaded as he is by the evidence, and his argument that if you’re eating “others” from over the mountain, then you’re not really eating people, cuts both ways. What better way to make people seem fundamentally different from “us” than to stress that “they” eat people? But that’s a topic for another episode, I hope.

Notes

- Food Fights & Culture Wars is currently riding high in Amazon’s New Releases.

- Lots more details on mayonnaise in Tom Nealon’s original account of Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War.

- To be honest, I had no idea mayonnaise was a topic of such intense interest, but it is.

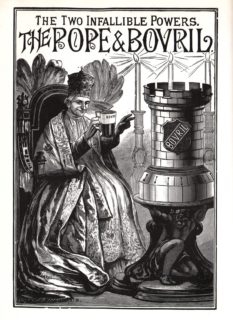

- For a fine collection of Bovril nonsense, this is the place.

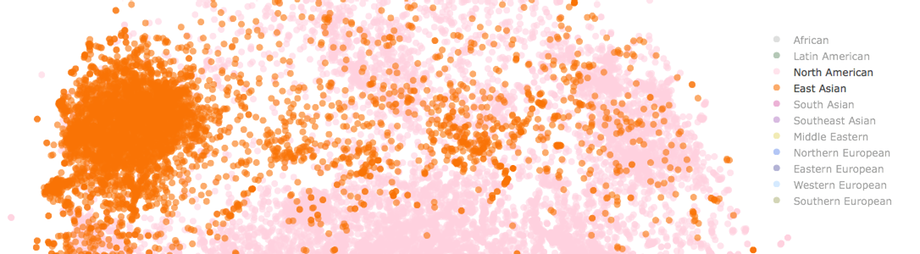

Recommendation engines are everywhere. They let Netflix suggest shows you might want to watch. They let Spotify build you a personalised playlist of music you will probably like. They turn your smartphone into a source of endless hilarity and mirth. And, of course, there’s IBM’s Watson, recommending all sorts of “interesting” new recipes. As part of his PhD project on machine learning, Jaan Altosaar decided to use a new mathematical technique to build his own recipe recommendation engine.

Recommendation engines are everywhere. They let Netflix suggest shows you might want to watch. They let Spotify build you a personalised playlist of music you will probably like. They turn your smartphone into a source of endless hilarity and mirth. And, of course, there’s IBM’s Watson, recommending all sorts of “interesting” new recipes. As part of his PhD project on machine learning, Jaan Altosaar decided to use a new mathematical technique to build his own recipe recommendation engine.