Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 24:21 — 20.0MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Nobody knows when the first apples were specifically selected in Ireland. The earliest written record dates to 1598, “when a writer discusses the fruitful nature of Irish orchards and the merits of the fine old Irish varieties contained in them”. (A brief history | Cider Ireland) The next couple of centuries saw a blossoming of native Irish apples, as farmers and landowners selected varieties that suited their conditions. In the middle of the 20th century, however, those myriad varieties began to be lost as consolidation and uniformity took hold.

Nobody knows when the first apples were specifically selected in Ireland. The earliest written record dates to 1598, “when a writer discusses the fruitful nature of Irish orchards and the merits of the fine old Irish varieties contained in them”. (A brief history | Cider Ireland) The next couple of centuries saw a blossoming of native Irish apples, as farmers and landowners selected varieties that suited their conditions. In the middle of the 20th century, however, those myriad varieties began to be lost as consolidation and uniformity took hold.

JGD Lamb (“informally known as Keith”) was one of the few people who worried about this loss. Lamb obtained his PhD in 1949 with a thesis entitled The Apple in Ireland: Its History and Varieties. In the process, he collected 53 old varieties, creating vigorous new trees by grafting them onto suitable rootstocks. These new trees formed the basis of the national collection at University College Dublin. Lamb also sent duplicates of many to the main apple breeding centre in the UK at Brogdale and it was just as well that he did, because some time later the UCD collection was grubbed up and destroyed. Whether by accident or design, nobody knows, but if it hadn’t been for the safety duplicates much of Lamb’s work would have been in vain.

In the early 1990s, Anita Hayes, founder of the Irish Seedsavers Association, launched a public hunt to recover the varieties Keith Lamb had collected and any that he missed. The end result was a restored national collection, the Lamb-Clarke collection at University College, Dublin, and the start of the Seedsavers own apple collection, which now numbers about 180 varieties. That includes 70 of Irish origin and the rest collected in Ireland but originally brought from elsewhere. And the hunt goes on. Roughly 50 Irish varieties that were documented in the past have so far not shown up.

Documentation is probably the hardest part of keeping a collection of apples (or any long-lived food) alive. Names change with time and place, memories fade, identities are appropriated and forgotten. DNA testing can tell you whether two samples are in fact one and the same, but not, as yet, any more than that. Meticulous, ongoing record-keeping gradually adds to the sum of knowledge but – as Eoin Keane explained in the podcast – sometimes it is a chance encouter that provides a vital bit of information that fleshes out an apple’s story. Unknown J, the apple I tasted and found so delicious, is no less delicious because we know nothing about it. But how much more would I like it if it had a romantic history to relate?

Notes

- I highly recommend a visit to the Irish Seedsavers Association in Scariff, County Clare.

- Tommy Hayes’ Apples in winter is “a celebration of the Irish apple in music, song, dance and film”. If I had my way I’d be enjoying it with a good russet and a sharp Cheddar, but that’s just me.

- Photos by me. The small one is Anita Hayes’ mystery medicinal apple.

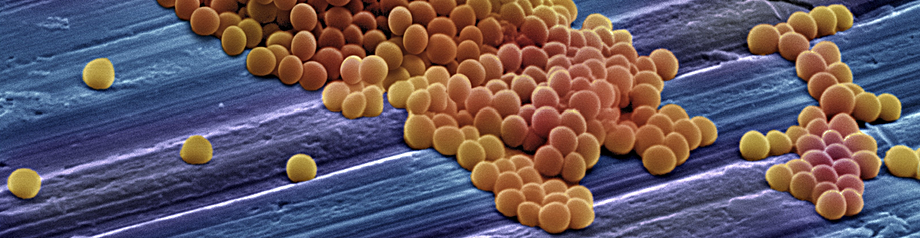

In the past year or so there has been a slew of high-level meetings pointing to antibiotic resistance as a growing threat to human well-being. But then, resistance was always an inevitable, Darwinian consequence of antibiotic use. Well before penicillin was widely available, Ernst Chain, who went on to win a Nobel Prize for his work on penicillin, noted that some bacteria were capable of neutralising the antibiotic.

In the past year or so there has been a slew of high-level meetings pointing to antibiotic resistance as a growing threat to human well-being. But then, resistance was always an inevitable, Darwinian consequence of antibiotic use. Well before penicillin was widely available, Ernst Chain, who went on to win a Nobel Prize for his work on penicillin, noted that some bacteria were capable of neutralising the antibiotic.