In the episode on Jewish Food in Rome I made much of the fact that many Jewish Roman dishes are found in restaurants across Rome and beyond. Not just carciofi alla giudia but others that are probably not recognised as Jewish, like cicoria ripassata and aliciotti con l’invidia. By contrast, one that has stayed in the former Ghetto, and indeed at a single location as far as I know, is pizza ebraica.

A slice of Jewish pizza is a chunky bar about 10cm long that is a dense confection of almonds and pine nuts with dried and candied fruit and raisins, baked very dark and crunchy. It is sold by the kosher bakery Boccione, which these days generally has a line out the door. A little goes a long way.

Sweet “pizza” is not an historic abomination, unlike the Nutella-topped creations across the river in Trastevere. Bartolomeo Scappi has recipes in his 16th century treatise, and the word pizza can encompass all sorts of dishes. Pizza ebraica is more formally known as pizza di beridde, traditionally baked to celebrate the bris, or circumcision, of a baby Jewish boy. Beridde is the Roman Jewish dialect for bris.

Boccione, despite being tiny, is unmissable even if there isn’t a line to point the way. It is on the corner as you enter the main street, via del Portico Ottavia, at the far end from the synagogue. And, unsurprisingly, the building has been there a long time, longer even than the 200 years that the bakery has been there.

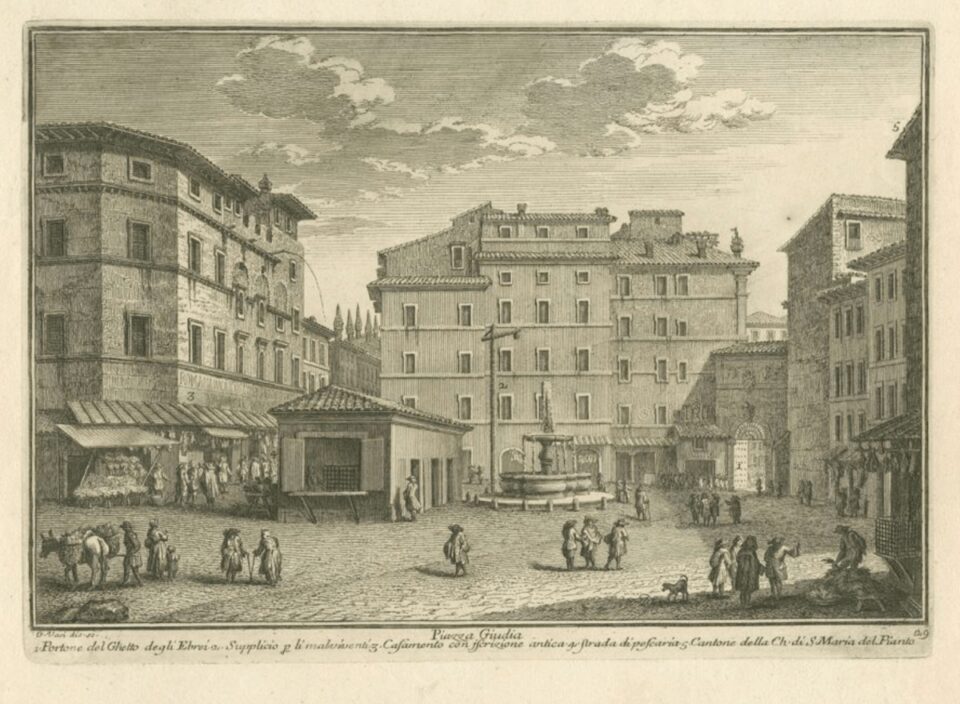

I was looking at a 1752 engraving by Giuseppe Vasi of the Piazza Giudia, which shows the Ghetto gate to the right, and my own photograph of Boccione, taken on a recent “research” visit. It’s a little tricky to get oriented, because the big fountain is no longer there, having been moved about 50 metres closer to the river in 1930 by order of Pope Pius XI. On the left of the engraving, though, is that distinctive chopped-off corner of the building and the number 3 and a Latin inscription. The words on the engraving look slightly different, but we all know artists edit what they see while the camera, of course, never lies.

So there it is, the forno del Ghetto, unique source of the stunningly good Jewish pizza. You can of course make it yourself, and dubious reverse-engineered recipes can be found online, but seriously, you owe it to yourself to buy a slice of the genuine article.

Today is the 80th anniversary of the roundup and deportation to Auschwitz of the Jews of Rome. That much I knew as I was planning this episode. More recent events took me and everyone else completely by surprise. I am sticking to my plan.

Today is the 80th anniversary of the roundup and deportation to Auschwitz of the Jews of Rome. That much I knew as I was planning this episode. More recent events took me and everyone else completely by surprise. I am sticking to my plan.

In her latest book English Food: A People’s History, Diane Purkiss offers just that, an entrancing survey of what and how the English ate, with due recognition that “‘the English’ are not a single entity” and that the past necessarily illuminates the present. Impossible to cover all that in a single episode, or even several, we set out to explore what happens when the vast bulk of the English do not have enough to eat. Food riots are a recurring feature of rural life in England, often the result of bad weather and always exacerbated by the action — or inaction — of the ruling classes. As Diane told me at the outset, “it might be faster to talk about what rebellions don’t have a food element”.

In her latest book English Food: A People’s History, Diane Purkiss offers just that, an entrancing survey of what and how the English ate, with due recognition that “‘the English’ are not a single entity” and that the past necessarily illuminates the present. Impossible to cover all that in a single episode, or even several, we set out to explore what happens when the vast bulk of the English do not have enough to eat. Food riots are a recurring feature of rural life in England, often the result of bad weather and always exacerbated by the action — or inaction — of the ruling classes. As Diane told me at the outset, “it might be faster to talk about what rebellions don’t have a food element”.

Anne Mendelson’s new book Spoiled is subtitled The Myth of Milk as Superfood, and at its core argues that while there’s nothing wrong with fresh milk, at least for those who can digest it as adults, the belief that you cannot have enough of a good thing has created a monstrous industry. Dairy farmers have always had the short end of the stick, because fresh milk is inevitably a buyers’ market. Cows have been manipulated to divorce them from any kind of natural life. And milk drinkers are being fobbed off with a tasteless white liquid reconstituted from its constituent parts and with no hedonic value. And for what?

Anne Mendelson’s new book Spoiled is subtitled The Myth of Milk as Superfood, and at its core argues that while there’s nothing wrong with fresh milk, at least for those who can digest it as adults, the belief that you cannot have enough of a good thing has created a monstrous industry. Dairy farmers have always had the short end of the stick, because fresh milk is inevitably a buyers’ market. Cows have been manipulated to divorce them from any kind of natural life. And milk drinkers are being fobbed off with a tasteless white liquid reconstituted from its constituent parts and with no hedonic value. And for what?