Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:07 — 25.9MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Remember Farm Aid, which launched in 1985? A lot of people do, and they tend to date the farm crisis in America to the 1980s, triggered by Earl Butz and his crazy love for fencerow to fencerow, get big or get out, industrial agriculture. And of course, land consolidation is inevitable, because if you’re going to invest in all that capital equipment to make your farm more efficient, you’re bound to buy up the smaller farmers who weren’t so savvy. Those “facts,” however, are anything but. They’re myths, on which much of the current criticism of American farm policy is built. There are others, too, and they’re all skillfully eviscerated by Nate Rosenberg and Bryce Wilson Stucki in a recent paper.

Remember Farm Aid, which launched in 1985? A lot of people do, and they tend to date the farm crisis in America to the 1980s, triggered by Earl Butz and his crazy love for fencerow to fencerow, get big or get out, industrial agriculture. And of course, land consolidation is inevitable, because if you’re going to invest in all that capital equipment to make your farm more efficient, you’re bound to buy up the smaller farmers who weren’t so savvy. Those “facts,” however, are anything but. They’re myths, on which much of the current criticism of American farm policy is built. There are others, too, and they’re all skillfully eviscerated by Nate Rosenberg and Bryce Wilson Stucki in a recent paper.

And here’s another thing. That first Farm Aid concert apparently raised $9 million. You could presumably help a lot of poor old dirt farmers with that kind of cash. But Farm Aid wasn’t actually about poor old dirt farmers, it was about people like Willie Nelson. He lost $800,000 the year before Farm Aid. Nine million dollars doesn’t go too far when individual people are losing that kind of money.

Notes

- The paper is The Butz Stops Here: Why the Food Movement Needs to Rethink Agricultural History, by Nathan A. Rosenberg and Bryce Wilson Stucki.

- John Biewen’s wonderful story about the Wise Family Farm in his series Five Farms tells the story of one black farmer in context. The family also featured in Biewen’s series Seeing White, all of which makes for disquieting and valuable listening. Gravy, the podcast from the Southern Foodways Alliance, also did a great episode on black land loss and systematic racism in the USDA.

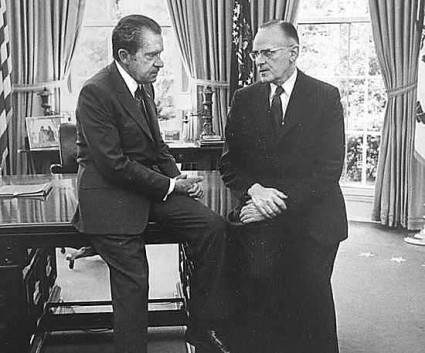

- I plundered various online archives for the clips of Jimmy Carter, Earl Butz and Willie Nelson.

- I owe a real debt of gratitude to Jonathan Kim for helping me to get a good clear recording of Bryce.

- When you want photographs of rural America in the 1930s, you turn to Dorothea Lange, so I did.

- Under no circumstances should you visit this page to see the utterly reprehensible use that popular culture made of Butz’s “gross indiscretion in a private conversation” which “in no way reflects [his] real attitude”.

Nobody knows when the first apples were specifically selected in Ireland. The earliest written record dates to 1598, “when a writer discusses the fruitful nature of Irish orchards and the merits of the fine old Irish varieties contained in them”. (

Nobody knows when the first apples were specifically selected in Ireland. The earliest written record dates to 1598, “when a writer discusses the fruitful nature of Irish orchards and the merits of the fine old Irish varieties contained in them”. (