- Genetic limits threaten chickpeas, a globally critical food; hummus-eaters, be afraid!

- Huge levels of antibiotic use in US farming revealed; Brexiteers cheer?

Eat This Newsletter 071 Pu'er missus

Outside of China, bitterness doesn’t represent hardship – it is the hardship.

There’s bitterness and bitterness, of course, but fundamentally, I disagree; bitterness is an easily learned delight. That’s not the point of Angie Lee’s fascinating essay Going going gan in the Cleaver Quarterly. It is about bitterness, of course, but also about growing up Chinese in America and about the elusive quality of gan, bitterness that is more than a mere taste. I’ll leave you to savour the whole thing, but one of the lessons I took away from it is that I have probably been doing pu’er tea all wrong.

In 2005, on a visit to Kunming, I was given a huge block of pu’er tea. A dozen years later, I still have masses left. The fact is, I know almost nothing about teas. I know enough to enjoy them, but I’m no connoisseur. I go through phases, too, drinking a meditative pot of something at the close of the afternoon for a few weeks, then giving it up. The something is usually pu’er or genmaicha and, probably because I have never had a tutored tasting, I’ve never experienced anything like the sensations Angie Lee gets when she drinks pu’er. I shall continue to drink it, of course, but going forward I don’t suppose I’ll ever think of it in quite the same way.

Have you been taught to appreciate tea, or anything else? I’d love to hear about it.

After tea, coffee’s hot number. Why is the number 5282 closely identified with coffee? A clue: it’s all to do with phone numbers. And vanity. And biopiracy. Let’s not forget Thomas Alva Edison. And the potential of an outbreak of measles to disrupt communications. All unravelled at Peter Giuliani’s Pax Coffea.

A book review to chew on Books about food and cooking remain a bright spot in publishing, with the result that, for me at least, they’ve becoming a bit like cooking shows on TV; something to absorb, passively, rather than something to motivate action in the kitchen. I was very pleased, then, to read Cynthia Bertelsen’s review of Samin Nosrat’s Salt Fat Acid Heat. I’ve seen a couple of others, of course, but this review actually made me want to buy the book. I know that’s not supposed to be the point of reviews (or is it?), but it is as good a reason to read them as any.

In the full-length Eat This Newsletter — find it online and subscribe there or here — the hummus crisis that isn’t and the beef-buying public.

From little seeds … How one country is sharing its edible history

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:49 — 15.7MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

No apologies for returning to the Irish Seed Savers Association in County Clare. An organisation like that usually sprouts from one person’s enthusiasm and drive, and it flourishes with the commitment and passion of volunteers and staff for whom the work is much more than a job. I spoke to Anita Hayes, who started ISSA, and Eoin Keane, who looks after the apple collection, in an episode last October. Today Anita and some of the people who are carrying her work forward talk some more about seed saving and the Irish Seed Savers Association.

A little context may be in order too. Why does something like ISSA need to exist? Can’t gardeners just buy the seeds they want in the shops? Short answer: no. Many of the seeds on offer to gardeners in Europe are varieties that were bred for commercial production. And older varieties, selected because they offered qualities valuable to home growers, cannot legally be offered for sale.

It’s a long story, and one that many people find hard to believe, but in essence the European Common Catalogue, established in the 1960s, says that any variety needs to be registered in order to be offered for sale, and the registration fee is the same for all varieties. That makes registration a trivial cost for a big-selling commercial variety and a huge drain on the profitability of a variety that appeals to even thousands of gardeners. As a result, gardeners in Europe had to establish their own living genebanks, finding, multiplying and distributing seeds using a variety of wheezes.

Ever since the Common Catalogue was first published there have been various attempts to open it up, and there has been some small movement. These experiments, however, still have not properly addressed the needs of home gardeners. Until they do, the Irish Seed Savers Association and organisations like it have a valuable job to do.

Notes

- You can visit the Irish Seed Savers Association website and, better yet, the place itself.

- In addition to Anita Hayes, in the episode you heard from Tony Kay, Flora Barteau, Janet Gooberman, Áine Ni Fhlatharta and Felice Rae. Thanks to them, to Jennifer McConnell, (who took the picture of me in the polytunnel) and to everyone else who welcomed me to ISSA.

- In case you missed it, here’s the episode about Ireland’s apple collection.

- The banner photo show’s Felice Rae’s favourite lettuce seeds, drying before she gets her hands on them.

- You can now search the Common Catalogue online and even see all the varieties that have been deleted since the catalogue came into existence.

- The music is 12 and 6, one of the tracks from AnTara, a collaboration between Tommy Hayes and Matthew Noone.

- Full disclosure: I was closely involved with one of the first such seed libraries in the UK and had a very small part in helping ISSA get on its feet. I’ve also written about it ad nauseam. What I would like Europe to do about agricultural biodiversity is probably the least negative place to start, if you’ve a mind to.

Eat This Newsletter 070 Hellzapoppin'

Oh to be young and free. Munchies, a website, reminisces about the Great Anti-Popcorn Hysteria of 1994. That was when the Centre for Science in the Public Interest announced that movie popcorn was very high in saturated fats, a revelation that was met with screaming headlines and a large — but very temporary — drop in cinema popcorn sales.

But while Munchies has the giggles poking fun at the whole episode, boring old me remembered another story, the one about popcorn lung and – like popcorn itself – once I started in on it, I just couldn’t stop. You can share my discoveries by reading the newsletter online.

In other news, the FDA is not allowed to define “the food commonly known as eggs”. Modern Farmer tells me so. Who knows what lurks behind that. Does that mean that an eggless emulsion of fats and liquids could in fact declare that it contained eggs if it weren’t trying to appeal to vegans?

If you enjoy my obsession with eggless mayonnaise, you’re going to love Tom Scocca’s detailed, evidence-based harangue against recipe writers [who] lie and lie and lie about how long it takes to caramelize onions. His conclusion:

In truth, the best time to caramelize onions is yesterday. … [T]hrow the onions in a crock pot and go to bed. In recipe time, that’s hours and hours. In your time, the time that matters, it’s less than five minutes.

That’s exactly how I feel about making my own bread. It takes a long time, but it is’t my time.

Flickr photo by Felix Stahlberg

Bread as it ought to be Seylou Bakery in Washington DC

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:10 — 23.3MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Jonathan Bethony is one of the leading artisanal bakers in America, but he goes further than most, milling his own flour and baking everything with a hundred percent of the whole grain. He’s also going beyond wheat, incorporating other cereals such as millet and sorghum in the goodies Seylou is producing. I happened to be in Washington DC just a couple of weeks after his new bakery had opened, and despite all the work that goes into getting a new bakery up and running, Jonathan graciously agreed to sit down and chat.

Jonathan Bethony is one of the leading artisanal bakers in America, but he goes further than most, milling his own flour and baking everything with a hundred percent of the whole grain. He’s also going beyond wheat, incorporating other cereals such as millet and sorghum in the goodies Seylou is producing. I happened to be in Washington DC just a couple of weeks after his new bakery had opened, and despite all the work that goes into getting a new bakery up and running, Jonathan graciously agreed to sit down and chat.

Gluten

Jonathan impressed me with his live-and-let-live attitude to people who want to be gluten-free. I can only imagine how depressing it must be to have people shun the food you have dedicated your life to making. As he said, “I’m not a poison dealer”. But it did add to the motivation to pursue long fermentations and 100% whole grain flour, which does seem overall to make breads more digestible.

The Goods

Seylou is open from Wednesday to Sunday and was shut on the day I visited, so there was no chance to try anything. A couple of weeks later we went back for a coffee and something to eat, the proof of the pudding and all that. I was truly blown away. The whole grain croissant was an astonishing revelation. I simply could not imagine anything made of whole wheat could be so light and airy and yet so flavoursome. Same goes for the millet cookie. If I hadn’t been told, I’m sure I would never have guessed that it wasn’t wheat, and it had none of the self-righteous heftitude that “good-for-you” goods often have.

The bread I tried at my friend’s house. It was obviously not as light as a croissant, nor would I have wanted it to be, but it was moist and chewy and again incredibly tasty. Also, filling. A single slice mid-morning took me well into the afternoon.

As a bread baker myself, perhaps the secret is in the difference between harder and softer wheats, as Jonathan said, and how softer wheats result in bigger flecks of bran, which can make getting a good open crumb more difficult. In Italy I’ll often demonstrate the presence of bran in wholewheat flour by sifting a small sample, leaving the bran behind. When I tried that recently with some high-quality US-milled wholewheat, there was almost no bran left behind. It had been truly pulverised. I’m still a ways away from buying a home mill, but now I’m wondering; if I sifted my Italian flour for a bake and blitzed the bran in a food processor, would that make for a lighter loaf?

Varieties

You might imagine that an artisanal baker who talks about respect for the farmers and all they do for the land and for their grains would be using only ancient heirloom varieties, handed down from one generation to the next and tightly adapted to the farms on which they grow. You’ld be right, but only partly so. One variety Jonathan bakes with is probably at least 200 years old. Another was born yesterday.

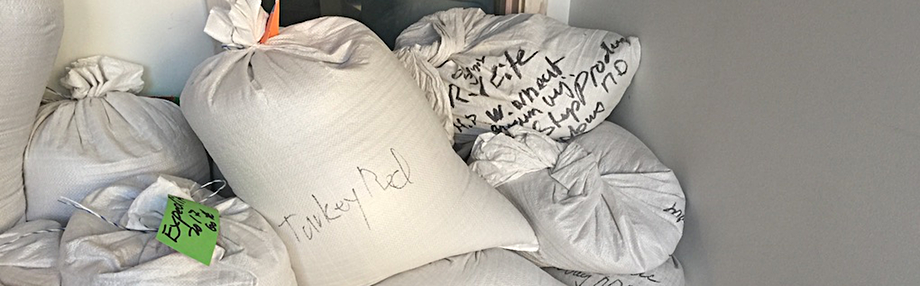

Turkey Red is a really old variety with a murky origin story, even after it reached the US. Some say that it was first planted in 1874 in Kansas by immigrant German-Russian farmers fleeing conscription in the Crimea, who brought it with them in their suitcases, trunks and special chests. Others credit a single farmer – Bernhard Warkentin – a German-speaking Mennonite from what is now Ukraine, who arrived in Kansas in the early 1870s scouting for good places to grow wheat. His father was a miller who had introduced Turkey Red to the area around Odessa in the Crimea, though nobody knows its history before that. While the early immigrants may have grown a little Turkey Red on their arrival, in 1885 and again in 1900 Warkentin was charged with importing “several thousand bushels of new seed” of Turkey Red from Crimea.

The variety became one of the foundations of the breadbasket states of the USA and a vital part of the economy of Kansas, but starting in the 1940s new, high-yielding varieties pushed it out to just a few small fields, the province of hobby farmers. In 2009 Slow Food USA added it to the Ark of Taste and that heralded something of a rennaissance, with Turkey Red finding new places to grow, close enough to Washington DC for Jonathan to consider it local.

Appalachian White sounds as it if could have much the same back story, but it’s ancestry is very different, and much better known. Its parents are KS2016-U2 and Lakin, themselves both relatively modern Kansas varieties, crossed deliberately to create a hard white winter wheat that would thrive in the eastern United States, where the climate is much damper than on the plains. The USDA released it to farmers in 2010 and it is now being grown quite widely in North Carolina and Virginia. Not as glamorous as Turkey Red, but also much more useful to farmers, millers and bakers on the east coast, especially those who want organic, local flour, which is exactly what the USDA breeders had in mind.

More

It was an article on NPR’s The Salt that first brought Seylou Bakery to my attention, followed after a bit of digging by a slightly earlier piece in The Washington Post. And here are three links to pieces in which Jonathan (and others) share what they know about baking good bread:

- Whidbey Bread: Whole Grains for the Home Baker, a Bread Lab workshop

- Could This Baker Solve the Gluten Mystery?

- 12 Tips from The Bread Lab, Where Baking is Like Playing an Instrument

As for the bakery’s back story, the Seylou website has that.