Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:48 — 22.7MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | | More

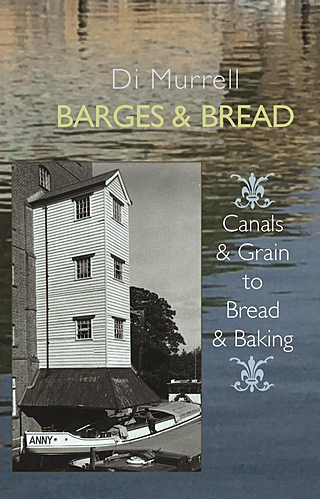

Time was, not so long ago, when you could barely move on the Thames in London for ships and boats of all shapes and sizes. Goods flowed in from the Empire in tall-masted sailing ships and stocky steamers and were transferred to barges and lighters for moving on. The canals, too, were driven by, and served, the industrial revolution, bringing coal and other raw materials to factories and taking away the finished goods by water, the cheapest and quickest system for bulk transport. By the late 1960s, much of the waterborne traffic had gone. Ships unloaded in the docks and goods were transferred by road and rail. A bit of freight continued to move on the water, some of that in the hands of Tam and Di Murrell. Di Murrell’s new book, Barges & Bread: canals & grain to bread & baking traces the interwined development of the grain trade and bread as it played out in the Thames basin and beyond.

Time was, not so long ago, when you could barely move on the Thames in London for ships and boats of all shapes and sizes. Goods flowed in from the Empire in tall-masted sailing ships and stocky steamers and were transferred to barges and lighters for moving on. The canals, too, were driven by, and served, the industrial revolution, bringing coal and other raw materials to factories and taking away the finished goods by water, the cheapest and quickest system for bulk transport. By the late 1960s, much of the waterborne traffic had gone. Ships unloaded in the docks and goods were transferred by road and rail. A bit of freight continued to move on the water, some of that in the hands of Tam and Di Murrell. Di Murrell’s new book, Barges & Bread: canals & grain to bread & baking traces the interwined development of the grain trade and bread as it played out in the Thames basin and beyond.

The importance of bread (and beer) to the people is encapsulated in the Assize of Bread and Ale, a statue of 1266 (though it appears to have codified earlier laws) and the first law in England to deal with food. Loaves were sold by size for a penny, a half-penny and, most commonly, a farthing (quarter of a penny). The finer the flour, the smaller the loaf you got at each price point. The price of grain naturally varied from year to year and from place to place, but the Assize fixed not the price but the weight of a penny loaf and also regulated in minute detail the baker’s profit and allowable expenses.

Very roughly, if the price of wheat was 12 pence a quarter (a quarter weighing 240 pounds) then the baker had to ensure that a farthing loaf of the best white bread, called Wastel bread, weighed 5.6 pounds. Wastel bread was not the most expensive. Simnel bread, “because it has been baked twice,” cost a bit more and so called French bread, enriched with milk and eggs, a bit more still. The coarsest “bread of common wheat” was less than half the cost of wastel bread.

From every quarter of wheat, the baker was permitted to sell 418 pounds of bread. Anything he could squeeze above that was called advantage bread, and was essentially pure profit. There was, naturally, every incentive for bakers and millers alike to add all sorts of things to increase the weight of flour and bread.

It is the connection between money and the weight of bread that is most intriguing. Weights, like money, were expressed as pounds. A pound in money was the pound-weight of silver, while the penny – the only coin in circulation – was a pennyweight of silver. But how much was a penny weight? 32 Wheat Corns in the midst of the Ear according to the Assize of Bread and Ale, which then explained that the 20 pence-weight made an ounce, and 12 ounces made one pound.

Notes

- Di Murrell’s book Barges & Bread: canals & grain to bread & baking, is available from Amazon and elsewhere, including direct from the publisher, Prospect Books.

- Di also has a website, Foodieafloat.

- If you really want to get to grips with the Assize of Bread, you need to read Alan S. C. Ross. “The Assize of Bread.” The Economic History Review, vol. 9, no. 2, 1956, pp. 332–342. JSTOR.

- Incidental music is the Impromptu from Zez Confrey’s Three Little Oddities, played by Rowan Belt

Huffduff it

Huffduff it

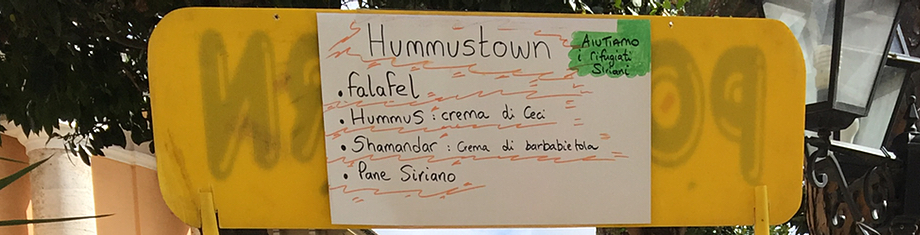

Refugees selling the food of their homeland to get a start in a new life is, by now, a cliché. Khaled (in the photo) joined their ranks a year ago. But cliché or not, selling food is an important way to give people work to do, wages, and hope. If it’s happening on your doorstep, which it is, and the food is good, which it is, what’s a hungry podcaster to do? Go there, obviously, and report back. Which is why, a couple of weeks ago, I found myself, microphone in hand, waiting patiently in line for a falafel wrap.

Refugees selling the food of their homeland to get a start in a new life is, by now, a cliché. Khaled (in the photo) joined their ranks a year ago. But cliché or not, selling food is an important way to give people work to do, wages, and hope. If it’s happening on your doorstep, which it is, and the food is good, which it is, what’s a hungry podcaster to do? Go there, obviously, and report back. Which is why, a couple of weeks ago, I found myself, microphone in hand, waiting patiently in line for a falafel wrap.

Time was, not so long ago, when you could barely move on the Thames in London for ships and boats of all shapes and sizes. Goods flowed in from the Empire in tall-masted sailing ships and stocky steamers and were transferred to barges and lighters for moving on. The canals, too, were driven by, and served, the industrial revolution, bringing coal and other raw materials to factories and taking away the finished goods by water, the cheapest and quickest system for bulk transport. By the late 1960s, much of the waterborne traffic had gone. Ships unloaded in the docks and goods were transferred by road and rail. A bit of freight continued to move on the water, some of that in the hands of Tam and Di Murrell. Di Murrell’s new book, Barges & Bread: canals & grain to bread & baking traces the interwined development of the grain trade and bread as it played out in the Thames basin and beyond.

Time was, not so long ago, when you could barely move on the Thames in London for ships and boats of all shapes and sizes. Goods flowed in from the Empire in tall-masted sailing ships and stocky steamers and were transferred to barges and lighters for moving on. The canals, too, were driven by, and served, the industrial revolution, bringing coal and other raw materials to factories and taking away the finished goods by water, the cheapest and quickest system for bulk transport. By the late 1960s, much of the waterborne traffic had gone. Ships unloaded in the docks and goods were transferred by road and rail. A bit of freight continued to move on the water, some of that in the hands of Tam and Di Murrell. Di Murrell’s new book, Barges & Bread: canals & grain to bread & baking traces the interwined development of the grain trade and bread as it played out in the Thames basin and beyond.