Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:42 — 17.6MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Shortly after the end of World War 2 in Europe, one of the quintessential boffins who had worked on the war effort turned his attention to the most pressing problem of the peace: a shortage of coal and oil. But where others saw the problem as a lack of transport, Geoffrey Pyke, saw a much more fundamental problem; a lack of food. Food required transport, and there was no fuel to power the engines. Pyke came up with a solution. Use the chemical energy in food to fuel muscular engines.

Shortly after the end of World War 2 in Europe, one of the quintessential boffins who had worked on the war effort turned his attention to the most pressing problem of the peace: a shortage of coal and oil. But where others saw the problem as a lack of transport, Geoffrey Pyke, saw a much more fundamental problem; a lack of food. Food required transport, and there was no fuel to power the engines. Pyke came up with a solution. Use the chemical energy in food to fuel muscular engines.

This episode is an abbreviated version of a paper on Food as Power: An Alternative View, which I am presenting on 30 May 2018 at the Dublin Gastronomy Symposium. The entire symposium is on Food and Power, so what’s alternative about my view? Pyke’s insight, that the production and transport of food requires muscular power, remains true today, and despite the very clear evidence and advice that Pyke offered in 1946, it also remains more or less ignored.

Muscles versus steam engines

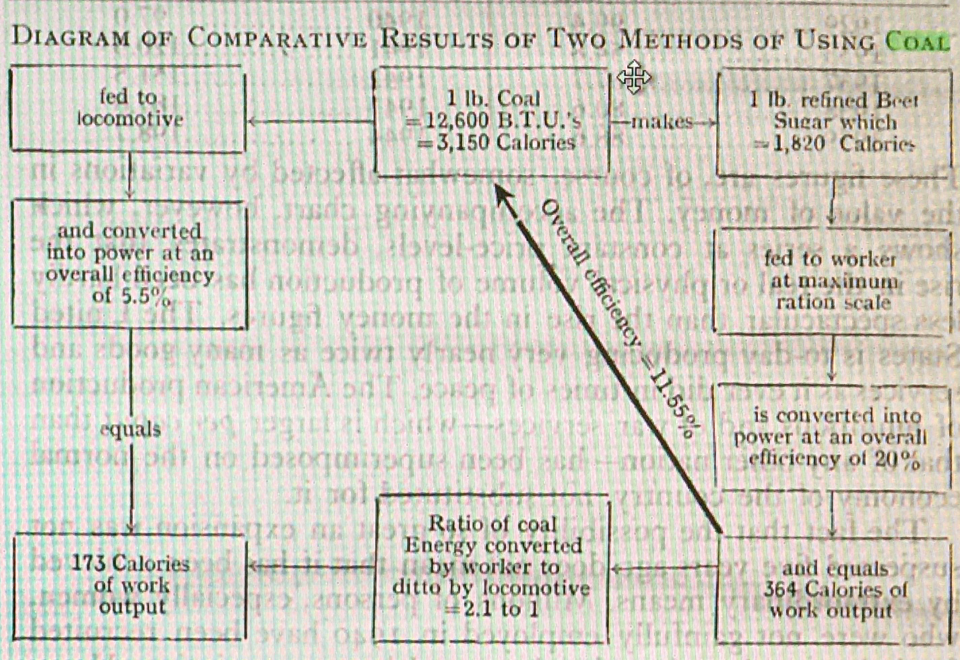

A crucial part of Pyke’s argument is the greater efficiency of muscles compared to steam engines, and that slips by relatively quickly in the podcast. So, here’s the diagram that Pyke published in The Economist

And here’s the detailed logic:

A pound of coal contains about 3150 calories, and if fed directly into a steam engine will produce about 175 calories of useful work. A pound of coal can also be used to refine sugar beets, in which case it will produce about a pound of sugar. The sugar contains about 1820 calories. Feed that to a man, and his muscles can turn it into about 365 calories of useful work. The man’s overall efficiency is about 11.5 percent, versus the steam engine’s 5.5 percent. Convert the coal into sugar, then, and you can get twice the useful work out of people than if you feed the coal to a steam engine.

Pyke argued that it would be “more economic, and politically necessary” to use what little coal there was to refine beet sugar than to power locomotives. And, as he sagely pointed out:

Half of the sugar–given the appropriate equipment– would be needed for the haulers taking the place of the steam engines, but the other half would be available to feed other workers such as coal miners, whose present output is so heavily reduced for want of food.

Muscles still do most of the work

Seventy years on, FAO estimates that muscles still provide 94 percent of the energy for global food production, about one-third animal muscle and two-thirds human muscle. One of the abiding problems is that women, who produce much of the food in sub-Saharan Africa, often have no choice but to use inefficient tools, designed for and bought by men. So metaphorical power also is relevant. But perhaps the saddest observation is that engineers have done masses of work to create tools and machines that make better use of the muscular power supplied by smallholder farmers and draught animals. These tools and machines have proved themselves in manifold trials on experimental stations, but they are ignored by the farmers for whom they were developed. The Colonial Office, in 1946, warned Pyke that it would be the people, not the equipment, that might pose a problem, and so it has proved. One report I read was rather plaintively subtitled “Perfected but rejected”.

Notes

- The 2018 Dublin Gastronomy Symposium on Food and Power takes place on 29 and 30 May 2018.

- My own paper Food As Power: an Alternative View is available for download, as are many of the other contributions.

- Music from Podington Bear.

In the previous episode, I talked to Phil Howard of Michigan State University about concentration in the food industry. Afterwards, I realised I had been so taken up with what he was telling me that I forgot to ask him one crucial question.

In the previous episode, I talked to Phil Howard of Michigan State University about concentration in the food industry. Afterwards, I realised I had been so taken up with what he was telling me that I forgot to ask him one crucial question.