Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 16:02 — 13.2MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

In the previous episode, I talked to Phil Howard of Michigan State University about concentration in the food industry. Afterwards, I realised I had been so taken up with what he was telling me that I forgot to ask him one crucial question.

In the previous episode, I talked to Phil Howard of Michigan State University about concentration in the food industry. Afterwards, I realised I had been so taken up with what he was telling me that I forgot to ask him one crucial question.

Is there any effect of concentration on public health or food safety?

It seems intuitively obvious that if you have long food chains, dependent on only a few producers, there is the potential for very widespread outbreaks. That is exactly what we are seeing in the current outbreaks of dangerous E. coli on romaine lettuce and Salmonella in eggs. But it is also possible that big industrial food producers both have the capital to invest in food safety and face stiffer penalties when things go wrong.

Are small producers and short food chains better? Marc Bellemare, at the University of Minnesota, has uncovered a strong correlation between some food-borne illnesses and the number of farmers’ markets relative to the population.

Phil thinks one answer is greater decentralization. There’s no good reason why all the winter lettuce and spinach in America should come from a tiny area around Yuma, Arizona. Marc says consumer education would help; we need to handle the food we buy with more attention to keeping it safe. Both solutions will take quite large changes in behaviour, by government and by ordinary people.

Right now, it probably isn’t possible to say with any certainty whether one system is inherently safer than the other. But even asking the question raises some interesting additional questions. If you have answers, or even suggestions, let me know.

Notes

- Phil Howard’s work on food-borne illness is on his website.

- Marc Bellemare’s work on farmers’ markets and food-borne illness has gone through a few iterations. He’ll email you a copy of the final paper if you ask.

- An episode early last year looked at aspects of food safety in developing countries. Spoiler: shorter food chains are safer there.

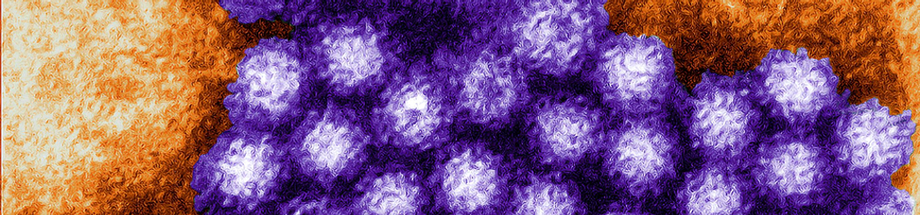

- Banner photo, norovirus. Cover photo, E. coli. Both public domain to the best of my knoweldge.