In the middle of Our Daily Bread, I got a message from Shelley at Against the Grain Farms in Canada. They’ve been working on restoring old varieties of wheat and barley for the past 31 years and they’re looking to contact farmers and researchers who would like to collaborate in some participatory plant breeding.

Winding Down Our Daily Bread 31

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 4:09 — 3.4MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

What more is there to say? Plenty, of course, but not this time. This is the final episode of this run of Our Daily Bread.

I say that as if there will be another, but all I’m really doing is leaving the door slightly ajar. I’ve had a lot of fun and learned a lot. I hope you have too.

For a final thought, I cannot do better than Elizabeth David, from her meticulous chapter on The Cost of Baking Your Own Bread in English Bread and Yeast Cookery. After going through nutrition, prices and all that she writes:

“So much for price comparisons. Long before you’ve finished doing the sums you realise that what counts is the value of decent bread to you and to the people you are responsible for feeding, and what that is, it’s up to us to work out for ourselves.”

A Perennial Dream Our Daily Bread 30

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 8:04 — 6.6MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Wheat is an annual plant; it dies after setting seed. Each year, the farmer has to prepare the land, sow seed, fertilise and protect the plants. When the ground is bare, between crops, wind and water can erode the soil. The shallow root systems of annual plants fail to exploit the resources of the soil and do little to improve it. So although wheat feeds us, it does so at considerable cost to the environment. It isn’t sustainable.

What if wheat were perennial?

Photo by Jerry D. Glover; annual wheat on the left, Kernza™ on the right.

It’s a Hard Grain Our Daily Bread 29

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 6:48 — 5.5MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Durum wheat is only about 5% of the total wheat harvest around the world. For those of us who like our pasta, that’s a very important 5%. Different gluten proteins make a durum dough stretchy rather than elastic — perfect for pasta. The kernels are very hard and need dedicated milling machinery, which produces small granules — semolina — rather than flour. That, however, may be about to change.

Photo of Soft Svevo from USDA, Pullman, WA.

Anything but Grim Our Daily Bread 28

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 7:09 — 5.8MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

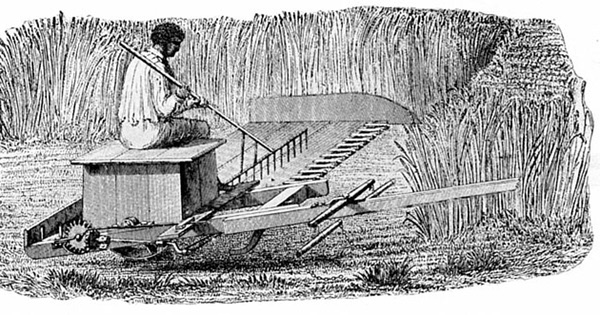

The one process in the whole business of turning wheat into bread when time is of the essence is the harvest. It’s back-breaking work, and the slightest delay can ruin the quality of the grain. In Europe, a ready supply of peasants got the job done. In America, labour, especially in the newly settled midwest, was extremely scarce. Inventors had to come up with machines.