Maybe you’ve seen the news that a Kernza crop failure has prompted General Mills to modify plans for a Kernza-based breakfast cereal. Instead of rolling out the product this year, the company is instead offering a box only to people who donate at least $25 to The Land Institute, the perennial crops organisation that has spent years developing Kernza.

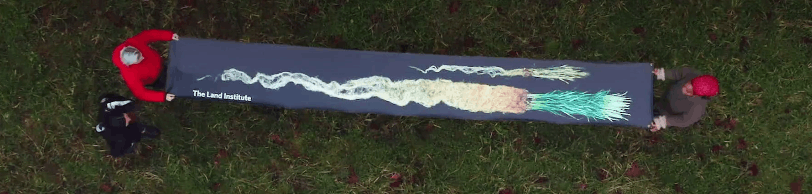

There are a couple of things about the story that intrigue me. First, for anyone who doesn’t know, Kernza is a perennial cousin of wheat, which offers several potential advantages over its annual cousin. Mostly, these are the result of being a perennial that develops a root system much more extensive than wheat’s. Not having to preopare the soil each year, along with that root system, means that Kernza can reduce soil erosion considerably. It also reduces the leaching of nitrogen from the soil. All that currently comes at a cost, though, because Kernza also yields less grain than wheat.

The 2018 harvest was even lower than expected, however, because of “weather and mistimed planting and harvesting decisions”. That’s unfortunate, but these are early days and further research will surely help farmers to make better decisions about when to sow and when to reap. What I don’t understand, and the article barely makes mention of it, is whether the crop, being perennial, will simply regenerate itself this year. If so, and I hope it will, that would be yet another advantage over annual wheat.

Wes Jackson, founder of The Land Institute, always talks of harvesting ready-mixed granola from a mixed stand of various perennial crops. [1] Honey toasted Kernza cereal isn’t quite that, but there are apparently 6000 boxes available. At $25 a pop, that should be $150,000 for more research. And eventually, Kernza cereal everywhere, and maybe even perennial granola.

-

He was already doing so when I visited, back in the 1980s. ↩

In matters of personal taste there are no absolutes. I like this, you like that. But does that also mean that there is no good, no bad? That is a surprisingly complex question, especially when it comes to as fundamental a food as bread. William Rubel is a freelance historian of food who seems to take a delight in pricking the pretensions of people like me, who think that some kinds of bread are better than others. “Why can’t we like what we like?” he asked in a defence of supermarket packaged bread. To which I say, “Like it if you like, but don’t tell me it is good.” He also says that there is no historical tradition of using a leaven among Anglophone bakers, which somehow diminishes the efforts of English-speaking bakers to “revive” the use of sourdough leavens and long fermentation. And that revival denigrates supermarket bread.

In matters of personal taste there are no absolutes. I like this, you like that. But does that also mean that there is no good, no bad? That is a surprisingly complex question, especially when it comes to as fundamental a food as bread. William Rubel is a freelance historian of food who seems to take a delight in pricking the pretensions of people like me, who think that some kinds of bread are better than others. “Why can’t we like what we like?” he asked in a defence of supermarket packaged bread. To which I say, “Like it if you like, but don’t tell me it is good.” He also says that there is no historical tradition of using a leaven among Anglophone bakers, which somehow diminishes the efforts of English-speaking bakers to “revive” the use of sourdough leavens and long fermentation. And that revival denigrates supermarket bread.

For a while, archaeologists treated the origins of agriculture – where it began, how it spread – as a minor element in the grand sweep of human history. That started to change with new techniques that could identify preserved plant remains, especially cereal seeds, in the detritus of archaeological digs. Then came the ability to tell what people had been eating by looking at the chemicals in their bones. And every day new discoveries in genetics add yet more details.

For a while, archaeologists treated the origins of agriculture – where it began, how it spread – as a minor element in the grand sweep of human history. That started to change with new techniques that could identify preserved plant remains, especially cereal seeds, in the detritus of archaeological digs. Then came the ability to tell what people had been eating by looking at the chemicals in their bones. And every day new discoveries in genetics add yet more details.