The introduction to a new report about livestock antibiotic resistance in Science states unequivocally that “There is a clear increase in the number of resistant bacterial strains occurring in chickens and pigs.” It also, somewhat disingenuously in my view, says “It is unclear what the increase in demand for antibiotics means for the occurrence of drug resistance in animals and risk to humans.”

It has been clear almost since the first deployment of antibiotics that resistance to them evolves, and that the more antibiotics are used, the more resistance we can expect. I well remember, back in 1982, Stuart Levy warning me and anyone else who would listen that the world was already a dilute solution of Tetracycline. Levy died earlier this month, and yesterday’s Washington Post carried a very good obituary. It gives the background to his ground-breaking research, published in 1976, that the routine use of antibiotics on a chicken farm resulted in resistant bacteria in people who lived nearby. I can imagine what he might say to this conclusion from this latest report:

Globally, 73% of all antimicrobials sold on Earth are used in animals raised for food. A growing body of evidence has linked this practice with the rise of antimicrobial-resistant infections, not just in animals but also in humans. Beyond potentially serious consequences for public health, the reliance on antimicrobials to meet demand for animal protein is a likely threat to the sustainability of the livestock industry, and thus to the livelihood of farmers around the world.

Little-known fact: Levy’s original study was funded by the Animal Health Institute, who hoped his results would support their view that routine antibiotics were useful and effective with no downside risks. As the Post’s obituary notes:

“Our study from 1976 was [and still is] the only prospective U.S. study on this, and industry didn’t want more studies,” Dr. Levy told the Scientist magazine in 2015. “They were upset that our data showed them to be wrong. This was highly political.”

Amen.

Eat This Podcast’s episode Antibiotics and agriculture examined this history of antibiotics on farms and one possible solution.

Porridge, for me, is made of oats, water, a bit of milk and a pinch of salt. Accompaniments are butter and brown sugar or, better yet, treacle, though I have nothing against people who add milk or even cream. So, while I’ve been aware of the inexorable rise of porridge in all its forms, I’ve been blissfully ignorant of the details. When I make, or eat, a risotto or a dal, I certainly don’t think of it as a porridge. Maybe now I will, and all because Laura Valli took the trouble to send me a copy of her research paper Porridge Renaissance and the Communities of Ingestion.

Porridge, for me, is made of oats, water, a bit of milk and a pinch of salt. Accompaniments are butter and brown sugar or, better yet, treacle, though I have nothing against people who add milk or even cream. So, while I’ve been aware of the inexorable rise of porridge in all its forms, I’ve been blissfully ignorant of the details. When I make, or eat, a risotto or a dal, I certainly don’t think of it as a porridge. Maybe now I will, and all because Laura Valli took the trouble to send me a copy of her research paper Porridge Renaissance and the Communities of Ingestion.

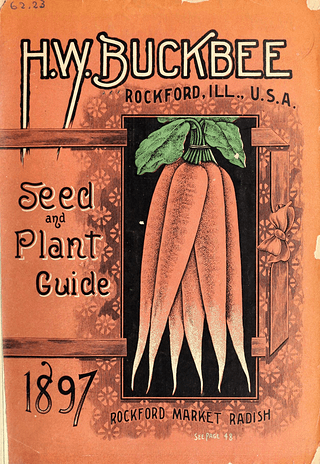

Earlier this summer, I learned about a talk at the annual conference of the American Society for Horticultural Science. The press release said it “holds all the intrigue of a murder mystery and all the painstaking, arduous pursuit of an archeological dig, along with a touch of serendipity”. And it concerned the rediscovery of a kind of radish that in its day was extremely famous. My kind of mystery. Naturally I had to talk to the sleuth cum Indiana Jones, Dr Gary Bachmann. Before I did so, though, I did a bit of digging of my own so that I’d be able to contribute a clue myself.

Earlier this summer, I learned about a talk at the annual conference of the American Society for Horticultural Science. The press release said it “holds all the intrigue of a murder mystery and all the painstaking, arduous pursuit of an archeological dig, along with a touch of serendipity”. And it concerned the rediscovery of a kind of radish that in its day was extremely famous. My kind of mystery. Naturally I had to talk to the sleuth cum Indiana Jones, Dr Gary Bachmann. Before I did so, though, I did a bit of digging of my own so that I’d be able to contribute a clue myself.