Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:10 — 19.4MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Taste has never really been purely subjective, good taste has always come with the baggage of social status and moral superiority. Perhaps nowhere is this more apparent than in politics, where the extended meanings of taste — refinement, discernment, judgement — brought with them an assumption that these were also the qualities associated with the ability to govern well. If you could choose a superior wine, of course you could choose a superior policy for the nation.

Chad Ludington, Professor of History at North Carolina State University, has studied the politics of wine in Britain extensively. He told me how changes in the production of wine, against the background of changes in political relationships between England and France and in the social structure of England, combined to make one’s choice of wine an important statement about one’s self-image.

In America, beer plays the part of wine in Britain, but the story is practically identical.

Notes

- Would you like a transcript?

- Professor Ludington’s book is The Politics of Wine in Britain: A New Cultural History.

- A few years ago we talked about How the Irish created the great wines of Bordeaux (and elsewhere).

- Food Fights, the book that prompted this episode, is published by University of North Carolina Press.

- Ale to the Chief (which is pretty clever) provides the background to Barack’s brews.

- Official White House photo by Pete Souza. Bottles of port by F. Tronchin on Flickr. Portrait of Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, by Jean-Baptiste van Loo.

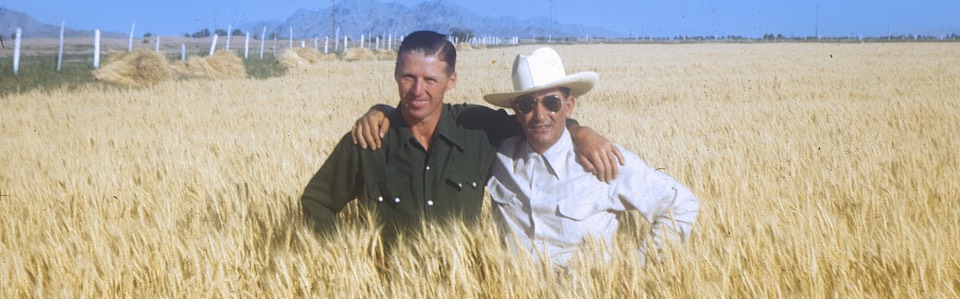

Norman Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work as a wheat breeder. The disease-resistant, dwarf wheats that he developed were the foundation of the Green Revolution, banishing global famine and turning India into a food-exporting nation. Many people have hailed Borlaug as a saint, a saviour of humanity. Others have blamed him for everything that is wrong with the modern global food system. The truth, naturally, lies somewhere in between, which is brought out in a new documentary about Borlaug and his work.

Norman Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work as a wheat breeder. The disease-resistant, dwarf wheats that he developed were the foundation of the Green Revolution, banishing global famine and turning India into a food-exporting nation. Many people have hailed Borlaug as a saint, a saviour of humanity. Others have blamed him for everything that is wrong with the modern global food system. The truth, naturally, lies somewhere in between, which is brought out in a new documentary about Borlaug and his work.