Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:02 — 27.6MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Think of Szechuan food and you think of hot and spicy, chilli-laden dishes. At least, I do. Chilli pepper is firmly established as the most widely used spice around the world, and nowhere more so than in China. And yet, chillies were unknown in China before about 1570. They arrived by at least three different routes, almost certainly more than once in each area, and found favour with ordinary Chinese people extremely rapidly. The ruling classes were not nearly as taken with them, and by and large failed to understand their importance. That contrast lasted through the first two centuries of the chilli in China, although it did not stop chillies eventually permeating Chinese culture high and low. For the people of Szechuan and Hunan, they became an essential part of their identity.

All this, and much, much more, comes from a new book by Professor Brian Dott, of Whitman College in Washington State. He combed through ancient texts and modern to trace the history of chillies in China and how they became such an essential element of life for so many people.

Notes

- Brian Dott’s book The Chile Pepper in China is published by Columbia University Press. This link will help you buy it from an independent bookshop in the US and this one in the UK. Both probably ship elsewhere too.

- You can download a transcript, thanks to the generosity of people who support the show financially. Think about joining them.

- I have no idea whether this version of Spicy Girls is a good one, but I thought I would share it anyway.

- Banner photo, by Xinhua, shows farmers in Gansu Province airing drying chillis. I got it here uncredited.

I’ll be honest, I thought I was pretty savvy about coffee taxonomy knowing that there were two kinds, arabica and robusta. Not surprisingly, perhaps, a research paper about “Coffea stenophylla and C. affinis, the Forgotten Coffee Crop Species of West Africa” caught my attention. And of course, as I should have known, there are scores of different coffee species. What is particularly intriguing about C. stenophylla, however, is that in its day people considered it a very fine coffee indeed. A 1925 monograph recorded that “The beans are said, by both the natives and the French merchants, to be superior to those of all other species.”

I’ll be honest, I thought I was pretty savvy about coffee taxonomy knowing that there were two kinds, arabica and robusta. Not surprisingly, perhaps, a research paper about “Coffea stenophylla and C. affinis, the Forgotten Coffee Crop Species of West Africa” caught my attention. And of course, as I should have known, there are scores of different coffee species. What is particularly intriguing about C. stenophylla, however, is that in its day people considered it a very fine coffee indeed. A 1925 monograph recorded that “The beans are said, by both the natives and the French merchants, to be superior to those of all other species.”

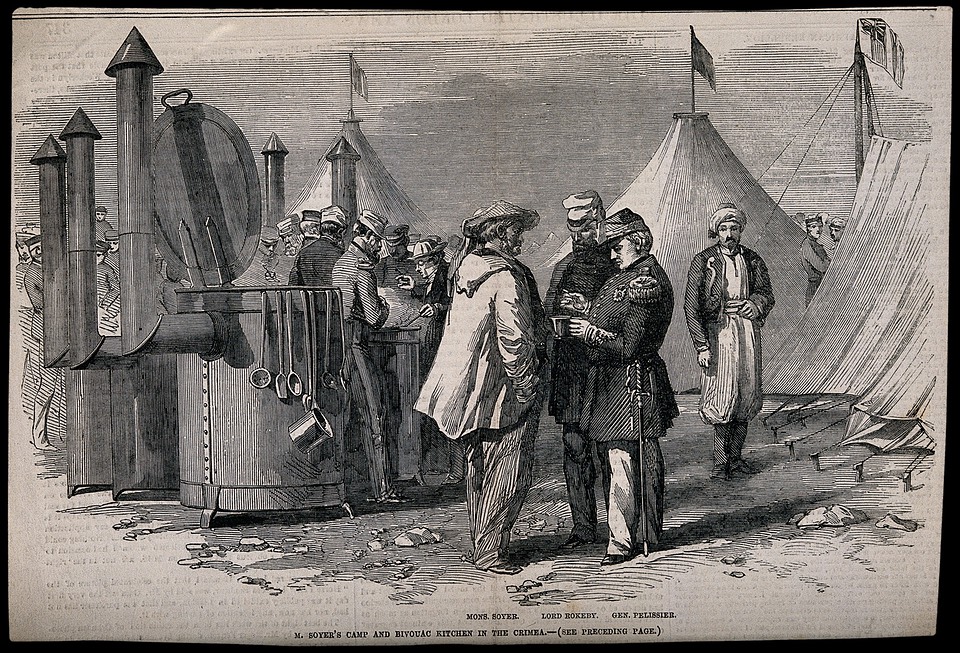

Alexis Soyer was perhaps the greatest chef of Victorian England. He designed the most modern kitchen of the 1840s and equipped it with many of his own inventions. He cooked unimaginably luxurious — and expensive — dinners for royalty and the aristocracy. He also built soup kitchens for the poor and his Famine Soup fed hundreds of thousands of destitute people in Ireland. His cookbooks sold in the hundreds of thousands, and sauces bearing his name brought luxury to the middle classes. He transformed British army cooking during the Crimean War, and the stove he invented for Crimea was still in use in the Gulf War in 1982. During the Crimean War, people said his name would live alongside Florence Nightingale’s. It didn’t, although lately Soyer, one of the first celebrity chefs, is being rediscovered.

Alexis Soyer was perhaps the greatest chef of Victorian England. He designed the most modern kitchen of the 1840s and equipped it with many of his own inventions. He cooked unimaginably luxurious — and expensive — dinners for royalty and the aristocracy. He also built soup kitchens for the poor and his Famine Soup fed hundreds of thousands of destitute people in Ireland. His cookbooks sold in the hundreds of thousands, and sauces bearing his name brought luxury to the middle classes. He transformed British army cooking during the Crimean War, and the stove he invented for Crimea was still in use in the Gulf War in 1982. During the Crimean War, people said his name would live alongside Florence Nightingale’s. It didn’t, although lately Soyer, one of the first celebrity chefs, is being rediscovered.