Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:29 — 21.6MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Timely to a fault, this episode comes out a couple of days after “farmers and meat lobbyists accuse plant-based food producers of ‘cultural hijacking’”. That’s in the EU, where this week the European Parliament will vote whether to ban the phrases “veggie burger“ and “veggie sausage,“ among others. Of course the plant-based food producers will have none of it, saying that “claims of consumer confusion are ridiculous”.

Timely to a fault, this episode comes out a couple of days after “farmers and meat lobbyists accuse plant-based food producers of ‘cultural hijacking’”. That’s in the EU, where this week the European Parliament will vote whether to ban the phrases “veggie burger“ and “veggie sausage,“ among others. Of course the plant-based food producers will have none of it, saying that “claims of consumer confusion are ridiculous”.

Are they, though? Maybe not for meat, but definitely for whole grain foods.

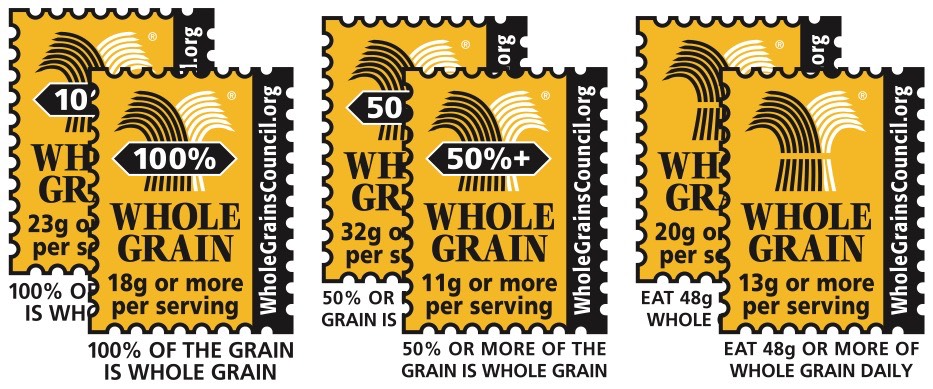

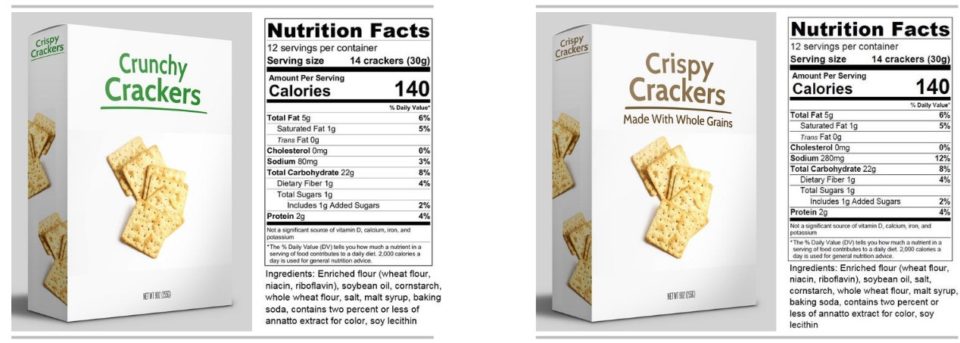

A recently published study showed that in the US consumers are indeed very easily confused by whole grain labels. In part, that’s because as long as you’re not actually lying, you can say things like “made with whole grains” without saying how much. There are industry-agreed labels, but they offer a fair amount of wiggle room too. So it isn’t really surprising that consumers often cannot decide which of two foods is “healthier”.

Parke Wilde, professor of US Food Policy at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University in Boston, told me about their research. We also talked about labels more generally.

Opponents of the EU proposals would prefer terms like “veggie disc” and “veggie tube”. I’m almost willing to bet real money that will never happen. But then there’s a whole ‘nother level of confusion, on which I do side with the farmers and the meat industry. Whatever you call them, plant-based discs and tubes are often touted as healthier alternatives, but given how much processing goes into their manufacture, and that — just like products “made with whole grains” — they may contain large quantities of things like salt, sugar and fat, are they really healthier than the red meat they might replace?

Notes

- Parke Wilde’s paper is Consumer confusion about wholegrain content and healthfulness in product labels: a discrete choice experiment and comprehension assessment, in the journal Public Health Nutrition.

- The episode transcript is here, thanks to supporters of the podcast.

- The Whole Grain Council’s page on Government Guidance is a good place to start exploring, if you want to learn more. That’s where I got the banner photo.

- Quotes about the looming EU battle from The Guardian.

- An earlier episode with Parke Wilde was How much does a nutritious diet cost?

I got an email from careme.co.nz and absolutely had to follow up. What was Carême, perhaps the first great French chef, doing in New Zealand? Turns out, he is Jo Crabb’s hero, so of course that’s what she named her cooking classes and her website. I wanted to find out more, and Jo was kind enough to agree to chat over, I must admit, a slightly dodgy connection.

I got an email from careme.co.nz and absolutely had to follow up. What was Carême, perhaps the first great French chef, doing in New Zealand? Turns out, he is Jo Crabb’s hero, so of course that’s what she named her cooking classes and her website. I wanted to find out more, and Jo was kind enough to agree to chat over, I must admit, a slightly dodgy connection.