Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 24:55 — 22.9MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Açai, goji, chia. Pepino, mangosteen, rambutan. Quinoa, teff, fonio. Names to conjure with, especially if you’re in the business of selling food dreams. All of them have been touted at one time or another as being the next big thing. Superfoods that can cure all the ills that ail you. Many more mundane foods — chocolate, coffee, red wine — have mutated into functional foods, imbued with power to promote good health and fight disease.

Açai, goji, chia. Pepino, mangosteen, rambutan. Quinoa, teff, fonio. Names to conjure with, especially if you’re in the business of selling food dreams. All of them have been touted at one time or another as being the next big thing. Superfoods that can cure all the ills that ail you. Many more mundane foods — chocolate, coffee, red wine — have mutated into functional foods, imbued with power to promote good health and fight disease.

“[B]etween 2011 and 2015 there was a phenomenal 202% increase globally in the number of new food and drink products launched containing the terms ‘superfood’, ‘superfruit’ or ‘supergrain’,” according to Mintel research.

Whether you believe the claims — I remain dubious — there’s one group of people that these foods could definitely help: the farmers who grow them. There are, however, reasons to be cautious.

A recent issue of the journal Choices brought together a set of case studies from Central and South America. I chatted to Trent Blare, one of the two editors of that issue, about some of the success stories and some of the difficulties.

Notes

- Choices Magazine Online: Functional Foods: Fad or Path to Prosperity?

- Chocolate really does “contribute to normal blood flow”.

- But here’s what Harvard School of Public Health thinks about superfoods.

- And that enlightened Swiss chocolate company Trent Blare mentioned? That would be Choba Choba.

- A transcript? Sure, as soon as it is ready.

- Cover photo by Neil Palmer/CIAT shows a lulo farmer in Darién, Colombia. Banner image of açai fruits in Brazil by Kate Evans/CIFOR.

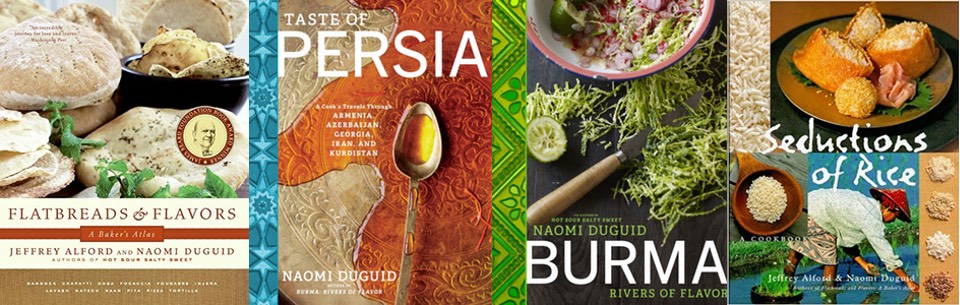

Photographer, writer, traveller, cook, geographer, culinary anthropologist: Naomi Duguid is all this, and more. True, her books contain approachable recipes that have won awards and accolades from food-first organisations, like the James Beard Foundation and the International Association of Culinary Professionals. But they also offer sensitive insights into the lives of people far from her native Canada. Why do they prepare, cook and eat the foods they do? How does the way they live influence the way they eat, and vice versa? And all illustrated with her photographs, at once both informative and atmospheric.

Photographer, writer, traveller, cook, geographer, culinary anthropologist: Naomi Duguid is all this, and more. True, her books contain approachable recipes that have won awards and accolades from food-first organisations, like the James Beard Foundation and the International Association of Culinary Professionals. But they also offer sensitive insights into the lives of people far from her native Canada. Why do they prepare, cook and eat the foods they do? How does the way they live influence the way they eat, and vice versa? And all illustrated with her photographs, at once both informative and atmospheric.