Arun Kapil casually mentioned “the very unfortunate cumin incident” in our conversation about his spice company, Green Saffron. I knew nothing about it, but didn’t pursue it at the time because it seemed too much of a diversion. Now that I’ve had a moment to do some digging, I understand why someone extolling the quality of their spices would be keen to distance themselves from tainted cumin, and quite right too.

So, what’s the story?

In October 2014, during a routine, random test of prepared foods, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency discovered traces of peanuts and almonds in packages of Ortega taco seasoning. Peanuts and almonds are bad allergens that can cause a severe reaction in susceptible people. The seasoning was pulled from grocery shelves and later tests in the US confirmed the presence of peanut protein in ground cumin and spice mixtures that contained ground cumin. The UK’s Food Standards Agency also found peanut in cumin powder and extended the contamination to powdered paprika.

People with allergies have trained themselves to look carefully at ingredients, but of course they’re looking for peanuts, not cumin. In any case, some spice mixtures give no indication of their contents, which can be treated as a trade secret and so never disclosed. The FDA advised people with severe peanut allergies to be very cautious and by February 2015 about 675 products, more than 500 from one company, were withdrawn. Nevertheless, the adulteration did cause problems for some people, and resulted in at least one lawsuit in Texas. But what were peanuts doing in ground cumin? And how did they get there?

Perhaps the contamination came from using second-hand sacks that had previously been used for peanuts. Or maybe the cumin-grinder or packing lines had seen some peanut action. However, the amounts involved make that extremely unlikely. In Canada, peanut amounted to about 0.5%, and even that is high for accidental contamination. In the US, tests detected 5% peanut, with some as high as 10%. That’s no accident.

People started to whisper about “economically-motivated adulteration”. Not with actual peanuts, which are a lot more expensive than cumin seeds, but with peanut shells, which can contain actual peanuts and which are essentially free. One consultant said that the place to look was at the very start of the chain; the grinder. “It doesn’t take too many $0 nut shells to bulk up profits on a cost/ounce product.”

Most versions of the story focused on unusually hot weather in Gujarat in 2014. Gujarat grows 75% of the cumin in India, and India grows 87% of the cumin in the world. The harvest in 2014 was disastrous, and prices began to rise steeply. But the contaminated cumin came from two companies in Turkey, the number two exporter of cumin in the world.

And there the trail peters out. Economically-motivated adulteration is a crime in the US. In the UK, newspaper reports filed the stories under “Crime” and it was the National Food Crime Unit (set up in the wake of the great horsemeat mislabelling scandal) that seemed to be handling the matter. Six years on, I have not been able to find any evidence of anyone being charged with anything.

Of course the Turkish companies could have imported cumin seed, or even ground cumin, from India before passing it on. That food industry consultant seems to think the problem lies in India, but his reasoning is somewhat dodgy to say the least:

The idea that this is an Indian-centric problem is supported by the observation that most in India do not understand food allergies, because they just don’t seem to happen to any great extent there. So the implication that adding a little peanut shell to cumin could kill someone in another country would just not register.

So what’s the current state of play? It seems that once the presence of peanuts had been detected and products recalled, contamination stopped being detected at high levels. There remains some, at around 20 parts per million, which is what you might expect if sacks are being reused or even if farmers are growing cumin and peanuts in rotation. Cumin prices have settled down again, I think, and exports continue to grow, with China a rising market. That law suit was settled out of court, secretly. Manufacturers are probably a bit more careful about monitoring their supplies, because nobody wants to slap a “may contain nuts” label on a package and drive away sensitive purchasers if they don’t have to.

The American Spice Trade Association offers this advice:

ASTA also recommends you and your customers become familiar with the old adage “it if seems too good to be true, it probably is” as it relates to the price of spices.

Which leaves only the question of what the true price of a spice should be.

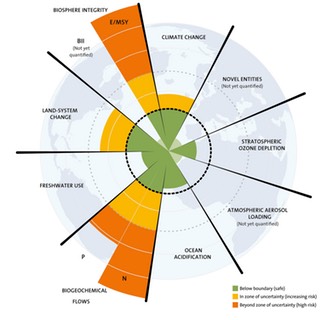

The idea of planetary boundaries, within which human life can “develop and thrive for generations to come”, was launched in 2009. Even then, we had crossed three boundaries, all intimately tied up with food production. But the process of “using up” resources, rather than simply making use of them, to supply our food is a much older pattern. In his book Diet for a Large Planet, Chris Otter, professor of history at Ohio State University, makes a powerful case that it was the British Empire that set the pattern, outsourcing the production of its food around the world. If food could be produced more cheaply elsewhere, then it made sense to do so, as long as the reckoning did not have to account for the wider costs.

The idea of planetary boundaries, within which human life can “develop and thrive for generations to come”, was launched in 2009. Even then, we had crossed three boundaries, all intimately tied up with food production. But the process of “using up” resources, rather than simply making use of them, to supply our food is a much older pattern. In his book Diet for a Large Planet, Chris Otter, professor of history at Ohio State University, makes a powerful case that it was the British Empire that set the pattern, outsourcing the production of its food around the world. If food could be produced more cheaply elsewhere, then it made sense to do so, as long as the reckoning did not have to account for the wider costs.

Midleton, in County Cork in Ireland, is not the kind of place where you would expect to find the headquarters of a growing global spice merchant. The farmers market in nearby Cork is where Arun Kapil and his wife Olive first started selling spices. Since then the company Green Saffron has grown steadily, drawing on Arun’s love of spices and family connections in India. It is still selling at farmers markets. But it is also shipping containers of carefully sourced spices to a European hub in Holland. And Arun told me that he has not compromised on quality along the way.

Midleton, in County Cork in Ireland, is not the kind of place where you would expect to find the headquarters of a growing global spice merchant. The farmers market in nearby Cork is where Arun Kapil and his wife Olive first started selling spices. Since then the company Green Saffron has grown steadily, drawing on Arun’s love of spices and family connections in India. It is still selling at farmers markets. But it is also shipping containers of carefully sourced spices to a European hub in Holland. And Arun told me that he has not compromised on quality along the way.

A little less than a year ago I talked to Professor Jeremy Haggar about his search for a forgotten coffee of Sierra Leone. It was a species called Coffea stenophylla, named for its narrower than usual leaves, which had an extremely good reputation a hundred years ago. Unfortunately it was not very productive and so, despite its excellent flavour, it was shoved out by much more productive robusta coffee. After quite a search, Haggar and his colleagues found a few plants, probably not more than 100 in total. Although they were delighted to have rediscovered stenophylla, they were disappointed that there were no coffee berries on the bushes.

A little less than a year ago I talked to Professor Jeremy Haggar about his search for a forgotten coffee of Sierra Leone. It was a species called Coffea stenophylla, named for its narrower than usual leaves, which had an extremely good reputation a hundred years ago. Unfortunately it was not very productive and so, despite its excellent flavour, it was shoved out by much more productive robusta coffee. After quite a search, Haggar and his colleagues found a few plants, probably not more than 100 in total. Although they were delighted to have rediscovered stenophylla, they were disappointed that there were no coffee berries on the bushes.