Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:29 — 23.5MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

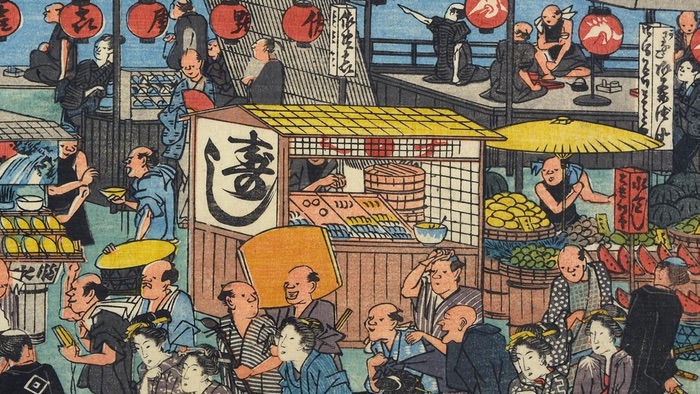

Eric Rath’s history of sushi traces the word back to its origins as a method of preserving fish through many twists and turns to today, when sushi means almost anything you want it to mean.

Notes

- Eric Rath’s book Oishii: The History of Sushi is published by Reaktion Books. It contains recipes old and new, in case you want to try making sushi at home.

- National Geographic surprised me with this article in early September: These popular tuna species are no longer endangered, surprising scientists.

- A popular culture view of modern sushi that I did not mention, precisely because it lives up to all possible stereotypes, is the amazing sequence in Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs. Almost more astonishing is the dedication that went into making it.

- Here is the transcript, thanks to the generosity of the show’s supporters.

- The banner image is a detail from Utagawa Hiroshige’s Amusements While Waiting for the Moon on the Night of the Twenty-sixth in Takanawa, which dates from the 1820s, with thanks to the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). The cover image is a detail from Bowl of Sushi, also by Hiroshige. I have not been able to date it.

Tomoca Coffee House in Addis Ababa is a lasting reminder of the Italian occupation of Ethiopia. When I visited, almost 10 years ago, a somewhat ancient machine was producing terrific cups of espresso for a huge crowd, and they were doing a roaring trade in beans too. Tomoca is in some ways a symbol not just of Ethiopian coffee, but also of the Italian connection and, at one remove, of the way that coffee ties Italy and Ethiopia to Brazil.

Tomoca Coffee House in Addis Ababa is a lasting reminder of the Italian occupation of Ethiopia. When I visited, almost 10 years ago, a somewhat ancient machine was producing terrific cups of espresso for a huge crowd, and they were doing a roaring trade in beans too. Tomoca is in some ways a symbol not just of Ethiopian coffee, but also of the Italian connection and, at one remove, of the way that coffee ties Italy and Ethiopia to Brazil.

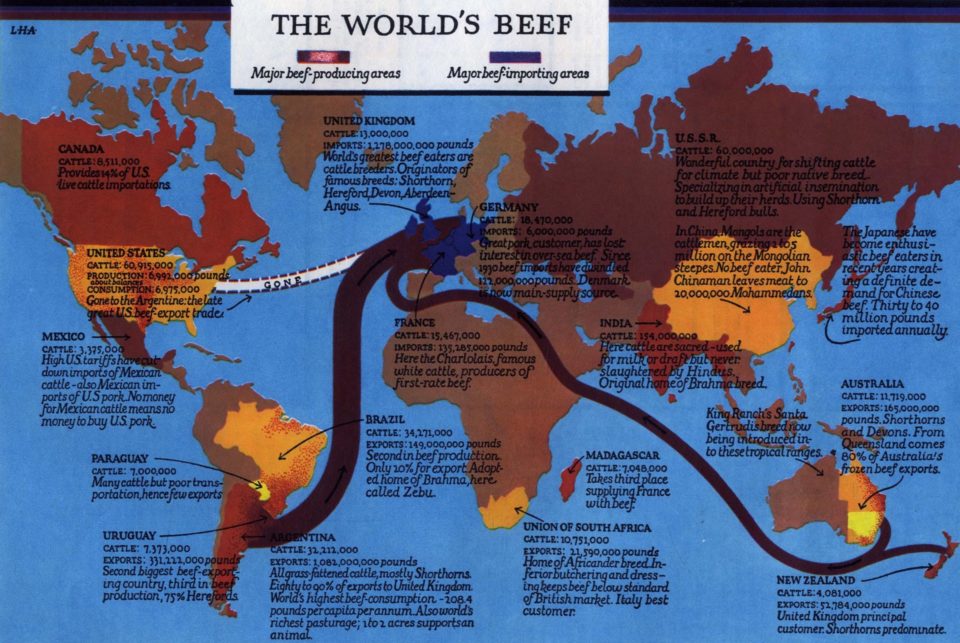

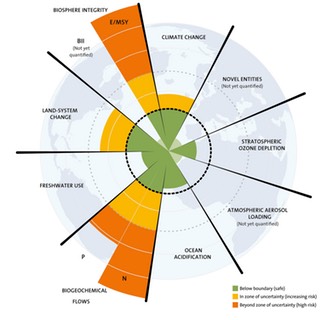

The idea of planetary boundaries, within which human life can “develop and thrive for generations to come”, was launched in 2009. Even then, we had crossed three boundaries, all intimately tied up with food production. But the process of “using up” resources, rather than simply making use of them, to supply our food is a much older pattern. In his book Diet for a Large Planet, Chris Otter, professor of history at Ohio State University, makes a powerful case that it was the British Empire that set the pattern, outsourcing the production of its food around the world. If food could be produced more cheaply elsewhere, then it made sense to do so, as long as the reckoning did not have to account for the wider costs.

The idea of planetary boundaries, within which human life can “develop and thrive for generations to come”, was launched in 2009. Even then, we had crossed three boundaries, all intimately tied up with food production. But the process of “using up” resources, rather than simply making use of them, to supply our food is a much older pattern. In his book Diet for a Large Planet, Chris Otter, professor of history at Ohio State University, makes a powerful case that it was the British Empire that set the pattern, outsourcing the production of its food around the world. If food could be produced more cheaply elsewhere, then it made sense to do so, as long as the reckoning did not have to account for the wider costs.