A paper in Nature Food today reports the results of a group of scientists in Finland who modelled the environmental impact of replacing animal-source foods in current European diets with novel or plant-based foods. They conclude:

Replacing animal-source foods in current diets with novel foods reduced all enviornmental impacts by over 80% and still met nutrition and feasible consumption constraints.

Behind that conclusion lie several assumptions about how novel and future foods might be scaled up and also about the “less favourable profiles” nutritionally speaking of pulses and grains. That said, the model’s results are interesting to say the least.

The team modelled three kinds of diet: all novel and future foods, omnivore and vegan. The bottom line seems to be that if you want a diet that minimises impacts on global warming, land use and water use while meeting nutritional requirements, you should eat an insect meal smoothie in cultured milk (i.e. made by cells in a bioreactor, not acted on by micro-organisms).

Given the difficulty, at least for me, of the full paper, I was glad to see an accompanying article, intended for the rest of us. Asaf Tzachor does a great job of explaining what these novel and future foods are and how the research “takes us one crucial step closer to dietary transition, starting in Europe”. He also says that “[f]ood regulators, standard setters and advisors … ought to be advised by this study,” but somehow I can’t help feeling that they — and we — still have a long way to go before any such transitions become an enticing reality.

Hoodwinked by hype

Some people, of course, are embracing some of the transitions on offer, although perhaps not quite yet the insect meal smoothie. Another recent report suggests that they might possibly have been hoodwinked by the hype around novel and future foods.

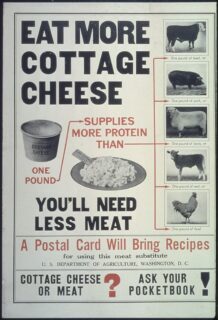

The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems — aka IPES-Food — has released its latest report on The Politics of Protein. As you might expect, it doesn’t pull any punches, saying fake meat “may not be as sustainable as its advocates claim” and pointing out that "[a] ‘protein obsession’ in marketing and media helps to bolster these technologies. A handy dandy factsheet distills some of the findings of the report, including the way Big Meat is investing in alternatives to ensure it becomes Big Protein, just in case that’s what people end up buying.

Well-meaning consumers of alternative proteins may not realise they’re buying into the same giant meat companies that are operating the biggest of factory farms, contributing to deforestation and forced labour, and slaughtering millions of animals everyday.

Personally, I’m reminded of the protein-requirement debates of the 1970s. While the recommended amounts vary according to age, health, activity levels etc. etc., by and large people in relatively well-off circumstances eat far more protein than they “need”. It seems to me that the emphasis on alternative sources of protein does little to address over-consumption. If anything, it probably promotes it.

As with so much of the food system, the problem is not how much is produced, but how it is distributed and to whom.

Last word to the Finnish researchers, with an irrefutable conclusion:

Our findings suggest that diets could be more land, water and carbon efficient if people would be amenable to more abstemious consumption.

A version of this post appeared first in Eat This Newsletter. Read previous issues and subscribe, should you wish.

Photo from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Many people take the myth of Demeter — Ceres in Latin — and her daughter Persephone to be just a metaphor for the annual cycle of planting and harvesting. It is, but there may be more to it than that. Why else would it be worth scaring participants in the Eleusinian Mysteries into saying absolutely nothing about what went on during these initiation rites into the cult of Demeter and Persephone?

Many people take the myth of Demeter — Ceres in Latin — and her daughter Persephone to be just a metaphor for the annual cycle of planting and harvesting. It is, but there may be more to it than that. Why else would it be worth scaring participants in the Eleusinian Mysteries into saying absolutely nothing about what went on during these initiation rites into the cult of Demeter and Persephone?

Senegal, on the western edge of Africa, was an ideal base for the transatlantic slave trade, although the European powers that established themselves in the region found other goods to trade too. One of the most important was the peanut, brought by Portuguese explorers to Africa, where it grew well, tended mostly by enslaved African labourers.

Senegal, on the western edge of Africa, was an ideal base for the transatlantic slave trade, although the European powers that established themselves in the region found other goods to trade too. One of the most important was the peanut, brought by Portuguese explorers to Africa, where it grew well, tended mostly by enslaved African labourers.

It is impossible to avoid the past in Rome; indeed, the past is why so many people come to Rome. If you’re interested in the history of food, though, there’s been nothing to see since the pasta museum shut its doors, aside from a few restaurants resting on their laurels. A new museum, at the bottom of the Palatine Hill and facing the chariot-racing stadium, has put food history back on the tourist map. I was very fortunate to get a guided tour from the director, Matteo Ghirighini, a few days before Garum, as it is called, opened its doors to the public. I learned so much, including the French origins of a Roman street food and the most convincing origin story yet for perhaps the most contentious pasta dish.

It is impossible to avoid the past in Rome; indeed, the past is why so many people come to Rome. If you’re interested in the history of food, though, there’s been nothing to see since the pasta museum shut its doors, aside from a few restaurants resting on their laurels. A new museum, at the bottom of the Palatine Hill and facing the chariot-racing stadium, has put food history back on the tourist map. I was very fortunate to get a guided tour from the director, Matteo Ghirighini, a few days before Garum, as it is called, opened its doors to the public. I learned so much, including the French origins of a Roman street food and the most convincing origin story yet for perhaps the most contentious pasta dish.