Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:30 — 28.9MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

In the final part of my conversation with Scott Reynolds Nelson, author of Oceans of Grain, we move on to empire. The earliest city states in Mesopotamia built their fortunes on their position astride grain transport routes. Still today, the ability to tax grain as it moves and to control that movement is a source of political and commercial power around the world. Nations also need to remember the need to feed the forces that exercise their power, which is often more important than materiel. And quite by coincidence, publication day celebrates the American War of Independence.

In the final part of my conversation with Scott Reynolds Nelson, author of Oceans of Grain, we move on to empire. The earliest city states in Mesopotamia built their fortunes on their position astride grain transport routes. Still today, the ability to tax grain as it moves and to control that movement is a source of political and commercial power around the world. Nations also need to remember the need to feed the forces that exercise their power, which is often more important than materiel. And quite by coincidence, publication day celebrates the American War of Independence.

Wrapping up this trilogy, I must add that there is much, much more to the story. It it impossible for me to single out any favourites, but I assure you that Oceans of Grain is well worth reading.

Notes

- Scott Reynolds Nelson’s book Oceans of Grain is published by Basic Books.

- In case you missed them, the first episode in this trilogy covers grain and transport and the second, grain and finance.

- Transcript, finally.

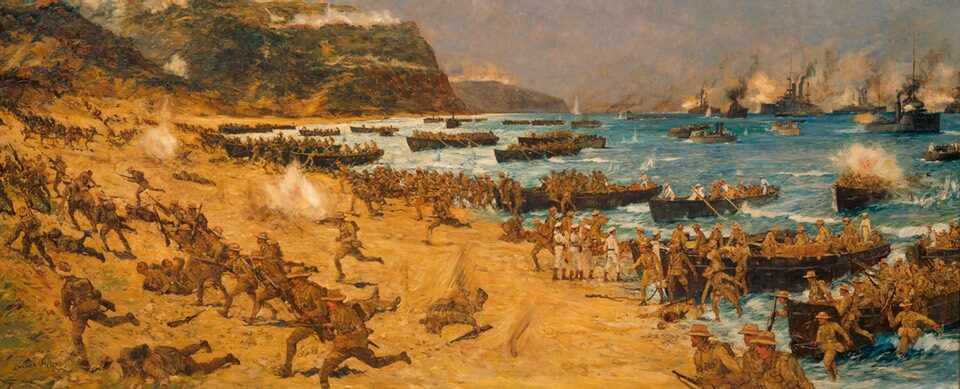

- Banner image from The landing at ANZAC, April 25 1915, by Charles Dixon. Cover image, a 1909 wheat penny, minted to commemorate the centenary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth and, not coincidentally, using wheat as a symbol of the United States’ empire.

Having moved your wheat from where it grew to where it was needed, there was a matching need to transfer the money to pay for it. Bills of exchange, invented in Venice and Genoa, created a piece of paper that increased in value as the time for delivery of the wheat drew near, but it was the need to avoid rank profiteering in times of war that created the futures market. Standard amounts of standard quality grain made buying and selling the crop even more efficient – and saved the Union army during the Civil War in the US.

Having moved your wheat from where it grew to where it was needed, there was a matching need to transfer the money to pay for it. Bills of exchange, invented in Venice and Genoa, created a piece of paper that increased in value as the time for delivery of the wheat drew near, but it was the need to avoid rank profiteering in times of war that created the futures market. Standard amounts of standard quality grain made buying and selling the crop even more efficient – and saved the Union army during the Civil War in the US.

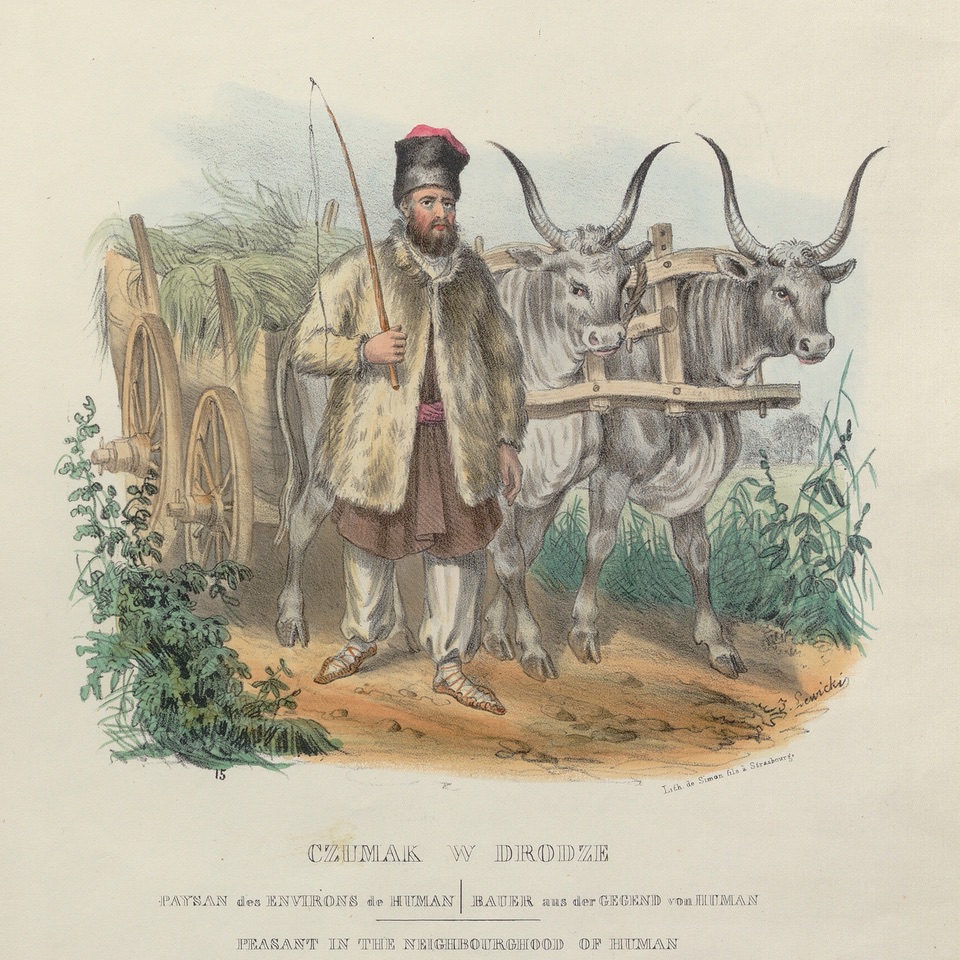

Cereals provide their offspring with a long-lived supply of energy to power the first growth spurt of the seed. Thousands of years ago, people discovered that they could steal some of the seeds to power their own growth, taking advantage of the storability of seeds to move the food from where it grew to where it might be eaten. Wheat, the pre-eminent cereal, moved along routes that were ancient before the Greek empire, carried, probably, by ox-drawn carts and guided along these black paths by people remembered in Ukraine today as chumaki.

Cereals provide their offspring with a long-lived supply of energy to power the first growth spurt of the seed. Thousands of years ago, people discovered that they could steal some of the seeds to power their own growth, taking advantage of the storability of seeds to move the food from where it grew to where it might be eaten. Wheat, the pre-eminent cereal, moved along routes that were ancient before the Greek empire, carried, probably, by ox-drawn carts and guided along these black paths by people remembered in Ukraine today as chumaki.

Many people take the myth of Demeter — Ceres in Latin — and her daughter Persephone to be just a metaphor for the annual cycle of planting and harvesting. It is, but there may be more to it than that. Why else would it be worth scaring participants in the Eleusinian Mysteries into saying absolutely nothing about what went on during these initiation rites into the cult of Demeter and Persephone?

Many people take the myth of Demeter — Ceres in Latin — and her daughter Persephone to be just a metaphor for the annual cycle of planting and harvesting. It is, but there may be more to it than that. Why else would it be worth scaring participants in the Eleusinian Mysteries into saying absolutely nothing about what went on during these initiation rites into the cult of Demeter and Persephone?

Senegal, on the western edge of Africa, was an ideal base for the transatlantic slave trade, although the European powers that established themselves in the region found other goods to trade too. One of the most important was the peanut, brought by Portuguese explorers to Africa, where it grew well, tended mostly by enslaved African labourers.

Senegal, on the western edge of Africa, was an ideal base for the transatlantic slave trade, although the European powers that established themselves in the region found other goods to trade too. One of the most important was the peanut, brought by Portuguese explorers to Africa, where it grew well, tended mostly by enslaved African labourers.