Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 33:22 — 30.7MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

A wet nurse (for that is what Hera was in all tellings of the story) created the Milky Way when her divine milk sprayed across the heavens. Today’s nursing mothers are not so blessed. Although women have a legal right to breastfeed in public across the United States and the UK (and many other countries), there are plenty of individuals who seem to think that they have the right to tell them to stop, and plenty of new mothers who are intimidated enough not to try. Why? How can this most essential of food chains possibly be considered shameful? And then there are the women who would dearly love to breastfeed their infants, but cannot. In this episode, experts on infant feeding discuss the history and current status of mothers’ milk and its various substitutes.

A wet nurse (for that is what Hera was in all tellings of the story) created the Milky Way when her divine milk sprayed across the heavens. Today’s nursing mothers are not so blessed. Although women have a legal right to breastfeed in public across the United States and the UK (and many other countries), there are plenty of individuals who seem to think that they have the right to tell them to stop, and plenty of new mothers who are intimidated enough not to try. Why? How can this most essential of food chains possibly be considered shameful? And then there are the women who would dearly love to breastfeed their infants, but cannot. In this episode, experts on infant feeding discuss the history and current status of mothers’ milk and its various substitutes.

Notes

- Professor Amy Brown’s website is full of amazing resources for and about nursing mothers.

- Lindsay Naylor is a political geographer. Her paper Troubling care in the neonatal intensive care unit and others prompted me to dig deeper.

- Professor Lawrence Weaver wrote White Blood: A History of Human Milk. His website “is a kind of autobiography”.

- There was no way I could cover the contamination at the Abbott infant formula plant. Helena Bottemiller Evich originally broke the story and has been following it closely. Her latest roundup sticks it to the Food and Drug Administration with a detailed accounting.

- The transcript has finally arrived.

Atkins. South Beach. Whole30. Zone. Keto. Banting? Yes, Banting. Not the Frederick Banting of Banting & Best, discoverers of insulin, but his distant relative William Banting, author, in 1863, of the self-published Letter on Corpulence, Addressed to the Public. Not the first fad diet by any means — Banting, a prominent London undertaker, had tried a bunch — it is the model, acknowledged and otherwise, for all the high-fat, low carbohydrate diets now so familiar and one of the first to seize the public imagination.

Atkins. South Beach. Whole30. Zone. Keto. Banting? Yes, Banting. Not the Frederick Banting of Banting & Best, discoverers of insulin, but his distant relative William Banting, author, in 1863, of the self-published Letter on Corpulence, Addressed to the Public. Not the first fad diet by any means — Banting, a prominent London undertaker, had tried a bunch — it is the model, acknowledged and otherwise, for all the high-fat, low carbohydrate diets now so familiar and one of the first to seize the public imagination.

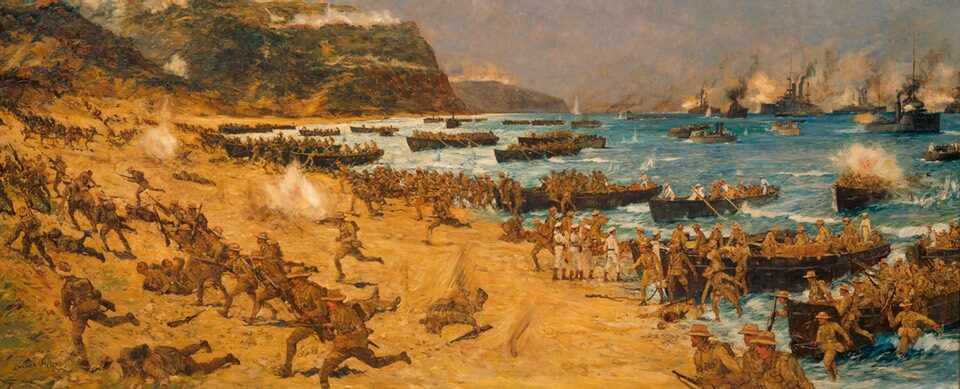

In the final part of my conversation with Scott Reynolds Nelson, author of Oceans of Grain, we move on to empire. The earliest city states in Mesopotamia built their fortunes on their position astride grain transport routes. Still today, the ability to tax grain as it moves and to control that movement is a source of political and commercial power around the world. Nations also need to remember the need to feed the forces that exercise their power, which is often more important than materiel. And quite by coincidence, publication day celebrates the American War of Independence.

In the final part of my conversation with Scott Reynolds Nelson, author of Oceans of Grain, we move on to empire. The earliest city states in Mesopotamia built their fortunes on their position astride grain transport routes. Still today, the ability to tax grain as it moves and to control that movement is a source of political and commercial power around the world. Nations also need to remember the need to feed the forces that exercise their power, which is often more important than materiel. And quite by coincidence, publication day celebrates the American War of Independence.

Having moved your wheat from where it grew to where it was needed, there was a matching need to transfer the money to pay for it. Bills of exchange, invented in Venice and Genoa, created a piece of paper that increased in value as the time for delivery of the wheat drew near, but it was the need to avoid rank profiteering in times of war that created the futures market. Standard amounts of standard quality grain made buying and selling the crop even more efficient – and saved the Union army during the Civil War in the US.

Having moved your wheat from where it grew to where it was needed, there was a matching need to transfer the money to pay for it. Bills of exchange, invented in Venice and Genoa, created a piece of paper that increased in value as the time for delivery of the wheat drew near, but it was the need to avoid rank profiteering in times of war that created the futures market. Standard amounts of standard quality grain made buying and selling the crop even more efficient – and saved the Union army during the Civil War in the US.

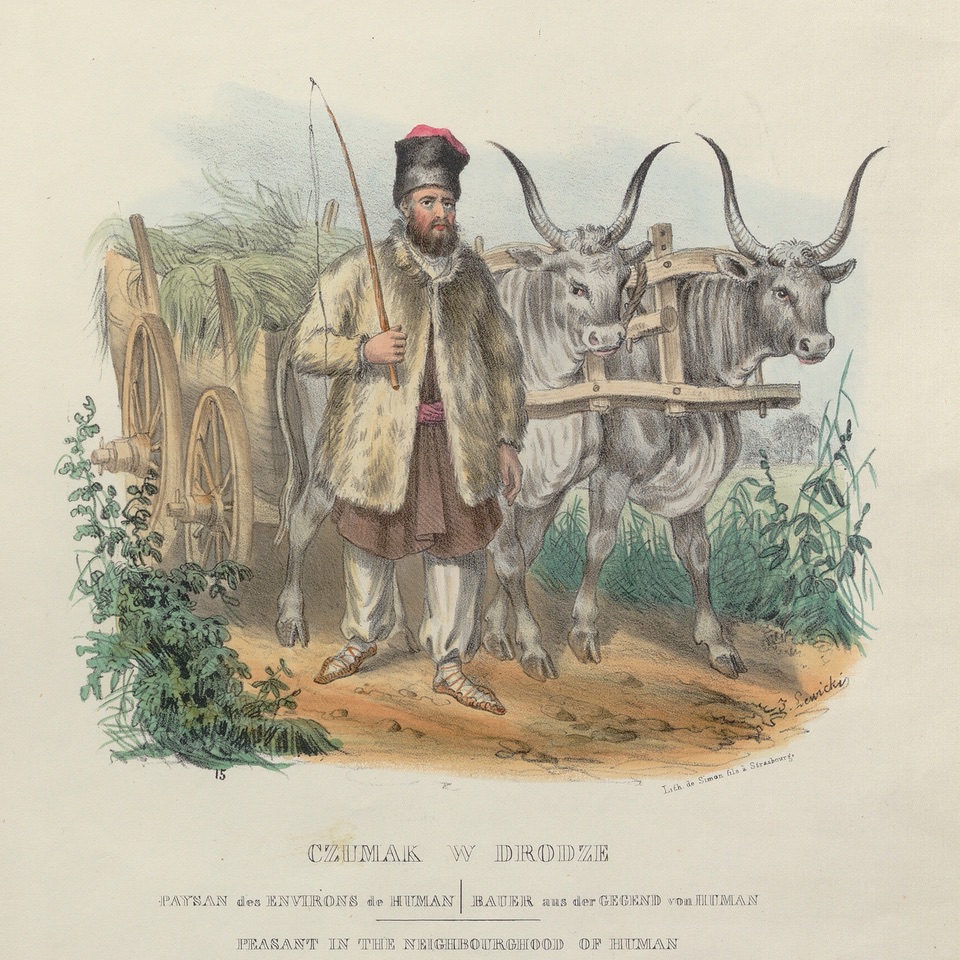

Cereals provide their offspring with a long-lived supply of energy to power the first growth spurt of the seed. Thousands of years ago, people discovered that they could steal some of the seeds to power their own growth, taking advantage of the storability of seeds to move the food from where it grew to where it might be eaten. Wheat, the pre-eminent cereal, moved along routes that were ancient before the Greek empire, carried, probably, by ox-drawn carts and guided along these black paths by people remembered in Ukraine today as chumaki.

Cereals provide their offspring with a long-lived supply of energy to power the first growth spurt of the seed. Thousands of years ago, people discovered that they could steal some of the seeds to power their own growth, taking advantage of the storability of seeds to move the food from where it grew to where it might be eaten. Wheat, the pre-eminent cereal, moved along routes that were ancient before the Greek empire, carried, probably, by ox-drawn carts and guided along these black paths by people remembered in Ukraine today as chumaki.