Italy, land of fabled wines, has seen an astonishing craft beer renaissance. Or perhaps naissance would be more accurate, as Italy has never had that great a reputation for beers. Starting in the early 1990s, with Teo Musso at Le Baladin, there are now more than 500 craft breweries in operation up and down the peninsula. Specialist beer shops are popping up like mushrooms all over Rome, and probably elsewhere, and even our local supermarket carries quite a range of unusual beers. Among them four absolutely scrummy offerings from Mastri Birai Umbri – Master Brewers of Umbria. And then it turns out that my friend Dan Etherington, who blogs (mostly) at Bread, cakes and ale, knows the Head Brewer, Michele Sensidoni. A couple of emails later and there we were, ready for Michele to give us a guided tour of the brewery.

Italy, land of fabled wines, has seen an astonishing craft beer renaissance. Or perhaps naissance would be more accurate, as Italy has never had that great a reputation for beers. Starting in the early 1990s, with Teo Musso at Le Baladin, there are now more than 500 craft breweries in operation up and down the peninsula. Specialist beer shops are popping up like mushrooms all over Rome, and probably elsewhere, and even our local supermarket carries quite a range of unusual beers. Among them four absolutely scrummy offerings from Mastri Birai Umbri – Master Brewers of Umbria. And then it turns out that my friend Dan Etherington, who blogs (mostly) at Bread, cakes and ale, knows the Head Brewer, Michele Sensidoni. A couple of emails later and there we were, ready for Michele to give us a guided tour of the brewery.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:40 — 25.6MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Mastri Birai Umbri is owned by the Farchioni family, which has become a powerhouse in basic agricultural products since the late 18th century. Farchioni olive oil is ubiquitous, and their flour only slightly less so, and while the quality of these products is high, they’re not the sorts of commodities I associate with a craft brewery. But I am starting to rethink the casual opposition between “industrial” and “craft” or “artisanal”. It’s true that industrial food processes are often soulless, repetitive and designed to serve only the bottom line, degrading the notion of quality about as far as it will go before people revolt. But my conversation with Michele showed me that it is possible to take an industrial approach to the production of a high-quality product. He insists on repeatability – that the brew should taste the same each batch and present the drinker with the same experience each time. That is probably the major distinction from a more artisanal or craft approach that instead of stomping out all the differences uses a different kind of skill to allow the product to vary slightly from batch to batch. The quality of Michele’s beer, however, is unimpeachable.

The other big distinction, I suppose, is quantity. When I asked him what the future might hold for craft beers in Italy, Michele thought it unlikely that 500 breweries could survive, because many are too small to compete. But why should that matter? If you’re big enough to survive at some scale, perhaps only in a local market, do you have to keep growing. This is one of those eternal business mysteries that I’ve seldom heard explained to my satisfaction. Why is perpetual growth necessary? Of course, demand may increase. But if you’re making as much as you want to and need to, and don’t want to regulate demand by increasing the price, that’s an opportunity for someone else to enter the market. You don’t have to do it yourself.

All of which is probably a bit deep for a consideration of well-made beers. In any case, I think I need to stop using “industrial” as a term of opprobrium and focus instead on the product, rather than the means of production.

Notes

- Le Baladin is a somewhat strange enterprise, and I am not as familiar with their beers as I would like to be. Their design sense is definitely quite odd. As Dan says, “It’s kinda scrappy, cartoony, vaguely Keith Haring, vaguely hippy, like someone’s mate did it, someone who’s not a professional designer. But remember kids, don’t judge a beer by its label.”

- No link to the Farchioni website, because it autoplays noise, and I hate that.

- The whole pure yeast vs wild fermentation debate is fascinating. Here’s a recent account from Australia: Winemakers turn to wild fermentation.

- Intro music by Dan-O at DanoSongs.com.

Bling, the

Bling, the

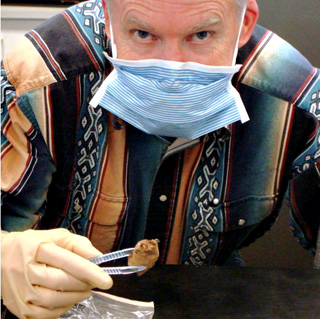

The Fertile Crescent, the Yangtze basin, Meso America, South America: those are the places that spring to mind as birthplaces of agriculture. Evidence is accumulating, however, to strengthen eastern North America’s case for inclusion. Among the sources of evidence, coprolites, or fossil faeces. Fossil human faeces. And among the people gathering the evidence Kris Gremillion, Professor of Anthropology at Ohio State University. She was kind enough to talk to me on the phone, and I made a silly mistake when I recorded it, so please bear with me on the less than stellar quality. I hope the content will see you through. And I’ll try not to let it happen again.

The Fertile Crescent, the Yangtze basin, Meso America, South America: those are the places that spring to mind as birthplaces of agriculture. Evidence is accumulating, however, to strengthen eastern North America’s case for inclusion. Among the sources of evidence, coprolites, or fossil faeces. Fossil human faeces. And among the people gathering the evidence Kris Gremillion, Professor of Anthropology at Ohio State University. She was kind enough to talk to me on the phone, and I made a silly mistake when I recorded it, so please bear with me on the less than stellar quality. I hope the content will see you through. And I’ll try not to let it happen again.