What, really, is the point of conserving agricultural biodiversity? The formal sector, genebanks and the like, will say it is about genetic resources and having on hand the traits to breed varieties that will solve the challenges tomorrow might throw up. Thousands of seed savers around the world might well agree with that, at least partially. I suspect, though, that for most seed savers the primary reason is surely more about food, about having the varieties they want to eat. David Cavagnaro has always championed that view. David’s is a fascinating personal history, which currently sees him working on the Pepperfield Project, “A Non-Profit Organization Located in Decorah, IA Promoting and Teaching Hands-On Cooking, Gardening and Agrarian Life Skills”. I first met David 15 or 20 years ago at Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah. This year, I was lucky enough to be invited there again, and I lost no time in finding time for a chat.

What, really, is the point of conserving agricultural biodiversity? The formal sector, genebanks and the like, will say it is about genetic resources and having on hand the traits to breed varieties that will solve the challenges tomorrow might throw up. Thousands of seed savers around the world might well agree with that, at least partially. I suspect, though, that for most seed savers the primary reason is surely more about food, about having the varieties they want to eat. David Cavagnaro has always championed that view. David’s is a fascinating personal history, which currently sees him working on the Pepperfield Project, “A Non-Profit Organization Located in Decorah, IA Promoting and Teaching Hands-On Cooking, Gardening and Agrarian Life Skills”. I first met David 15 or 20 years ago at Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah. This year, I was lucky enough to be invited there again, and I lost no time in finding time for a chat.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:07 — 11.2MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

David pointed out that immigrants are often keen gardeners and, perforce, seed savers as they struggle to maintain their distinctive food culture in a new land. That’s true for the Hmong in Minneapolis, Asian communities in England and, I’m sure, many others elsewhere. What happens as those communities assimilate? The children and grandchildren of the immigrant gardeners are unlikely to feel the same connection to their original food culture, and may well look down on growing food as an unsuitable occupation. Is immigrant agricultural biodiversity liable to be lost too? Efforts to preserve it don’t seem to be flourishing.

Seed saving for its own sake, rather than purely as a route to sustenance, does seem to be both a bit of a luxury and to require a rather special kind of personality. John Withee, whose bean collection brought David Cavagnaro to Seed Savers Exchange and people like Russ Crow, another of his spritual heirs, collect and create stories as much as they do agricultural biodiversity. And that’s something formal genebanks never seem to document.

Notes

- John Withee’s bean cookbook looks like it would be very interesting. Indeed, the whole Yankee bean-hole thing would be fun to explore.

- Are you aware of people adopting “immigrant” foods not just to eat, but to conserve? My mother-in-law had red shiso (Perilla frustescens) volunteers all over the place, although I’m pretty sure she never used it as a herb. The lemongrass on my balcony hardly counts.

- Can you point me to a public or private bean-hole party that might welcome a nosy reporter?

- Would you consider reviewing Eat This Podcast on iTunes?

- Or nominating it for a podcasting award?

- Intro music by Dan-O at DanoSongs.com.

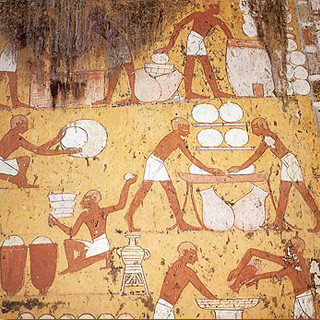

Say you wanted to bake bread in a microwave – I can’t think why, but say you did – you could go online and search the internets for a recipe. And you would come up with a few. Just reading them over, they didn’t seem all that appetising. One, for example, warned that you had to serve the bread toasted. What’s the point of that? Anyway, that didn’t deter Ken Albala, a professor at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, but rather than search the internet, he turned to ancient Egypt for inspiration. In thinking about ways in which the material culture of food might change in the future, for the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, he came up with not only

Say you wanted to bake bread in a microwave – I can’t think why, but say you did – you could go online and search the internets for a recipe. And you would come up with a few. Just reading them over, they didn’t seem all that appetising. One, for example, warned that you had to serve the bread toasted. What’s the point of that? Anyway, that didn’t deter Ken Albala, a professor at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, but rather than search the internet, he turned to ancient Egypt for inspiration. In thinking about ways in which the material culture of food might change in the future, for the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, he came up with not only  I am reliably informed that the taste of a soggy potato crisp – or chip, if you prefer – is identical to that of a crispy one. But the experience falls far short of enjoyable. A crisp needs to be, well, crisp. If it isn’t, it actually tastes bad. That’s not quite so true of things like fried or oven-roasted potato chips; they still taste pretty good when they’re not quite so crispy, but they’re even better when they are crispy, and that goes for a whole lot of other cooked crispy things too. Which is why it is such a shame that by the time you get to the bottom of a plateful of fries or nachos, they’re soggy. Not to mention thin-crust pizza in a box. Ken Albala, a food historian at the University of the Pacific in Stockton California, happens to be an accomplished ceramicist, so he invented a plate that helps keep foods crispy. And that prompted an episode on crispy crunchiness.

I am reliably informed that the taste of a soggy potato crisp – or chip, if you prefer – is identical to that of a crispy one. But the experience falls far short of enjoyable. A crisp needs to be, well, crisp. If it isn’t, it actually tastes bad. That’s not quite so true of things like fried or oven-roasted potato chips; they still taste pretty good when they’re not quite so crispy, but they’re even better when they are crispy, and that goes for a whole lot of other cooked crispy things too. Which is why it is such a shame that by the time you get to the bottom of a plateful of fries or nachos, they’re soggy. Not to mention thin-crust pizza in a box. Ken Albala, a food historian at the University of the Pacific in Stockton California, happens to be an accomplished ceramicist, so he invented a plate that helps keep foods crispy. And that prompted an episode on crispy crunchiness.

Carol Deppe was a guest here a few months ago, talking about how most people misunderstand the

Carol Deppe was a guest here a few months ago, talking about how most people misunderstand the  Italy, land of fabled wines, has seen an astonishing craft beer renaissance. Or perhaps naissance would be more accurate, as Italy has never had that great a reputation for beers. Starting in the early 1990s, with Teo Musso at Le Baladin, there are now more than 500 craft breweries in operation up and down the peninsula. Specialist beer shops are popping up like mushrooms all over Rome, and probably elsewhere, and even our local supermarket carries quite a range of unusual beers. Among them four absolutely scrummy offerings from Mastri Birai Umbri – Master Brewers of Umbria. And then it turns out that my friend Dan Etherington, who blogs (mostly) at

Italy, land of fabled wines, has seen an astonishing craft beer renaissance. Or perhaps naissance would be more accurate, as Italy has never had that great a reputation for beers. Starting in the early 1990s, with Teo Musso at Le Baladin, there are now more than 500 craft breweries in operation up and down the peninsula. Specialist beer shops are popping up like mushrooms all over Rome, and probably elsewhere, and even our local supermarket carries quite a range of unusual beers. Among them four absolutely scrummy offerings from Mastri Birai Umbri – Master Brewers of Umbria. And then it turns out that my friend Dan Etherington, who blogs (mostly) at