Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:47 — 19.5MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

A Dutch food writer tries to discover the origins of pom, the national dish of Suriname. Is it Creole, based on the foodways of Africans enslaved to work the sugar plantations of Surinam? Or is it Jewish, brought to Suriname by Dutch Jews?

A Dutch food writer tries to discover the origins of pom, the national dish of Suriname. Is it Creole, based on the foodways of Africans enslaved to work the sugar plantations of Surinam? Or is it Jewish, brought to Suriname by Dutch Jews?

So began Karin Vaneker’s immersion in the world of edible aroids. Aroids are a large and cosmopolitan plant family, more commonly known as the arum family, and they include some of the most familiar houseplants. Many of them have starchy roots or tubers, and although these often contain harmful substances, people have learned how to process them as famine foods. A few species, however, are widely cultivated. The best-known of these is probably taro, Colocasia esculenta, which originated in southeast Asia and spread through the Pacific and beyond. That, however, proved not to be the elusive pomtajer that Karin and the Surinamese inhabitants of Amsterdam were looking for, which turned out to be a species of Xanthosoma.

My conversation with Karin ranged far and wide, and to tell the truth I never did ask whether pom was Jewish or Creole. Most sources say it is indeed Jewish.

Notes

- The whole question of Jews in Suriname sent me scurrying to the search engines, to discover that starting in the 17th century there was indeed an attempt to establish an autonomous Jewish territory there, on the Jewish savanna. This I gotta read more about. And having found that, I rushed to Claudia Roden’s The Book of Jewish Food, only to be massively disappointed that neither pom nor Suriname feature in the index.

- The big photo is of purple-stemmed Colocasia, which I took at Longwood Gardens.

- As promised, a recipe for pom. You’ll have to find your own pomtajer.

- Karin has written on Cooking Pom and other edible aroids.

It is quite amazing how popular food tours and cooking classes are in Italy. When in Rome, many people seem to want to eat, and cook, like a Roman. Well, not entirely, and not like some Romans. I spoke to Francesca Flore, who offers both tours and cooking classes, and she reserved some choice words for those quintessential Roman dishes based on the famous quinto quarto, the fifth quarter of the carcass. Or, less obtusely, offal.

It is quite amazing how popular food tours and cooking classes are in Italy. When in Rome, many people seem to want to eat, and cook, like a Roman. Well, not entirely, and not like some Romans. I spoke to Francesca Flore, who offers both tours and cooking classes, and she reserved some choice words for those quintessential Roman dishes based on the famous quinto quarto, the fifth quarter of the carcass. Or, less obtusely, offal.

This episode of Eat This Podcast is something of a departure. With nothing in the pantry, so to speak, I had to make something with what I had: myself. So I hooked myself up to the audio recorder and went about some of my customary weekend cooking, muttering out loud about what I was doing and offering some reflections on my attitude to food and cooking. I hope the result sheds some light on where I’m coming from. Normal service will be resumed next episode.

This episode of Eat This Podcast is something of a departure. With nothing in the pantry, so to speak, I had to make something with what I had: myself. So I hooked myself up to the audio recorder and went about some of my customary weekend cooking, muttering out loud about what I was doing and offering some reflections on my attitude to food and cooking. I hope the result sheds some light on where I’m coming from. Normal service will be resumed next episode.

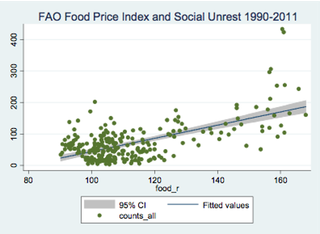

“If you can tell your story with a graph or picture, do so,” says Marc Bellemare, my first guest in this episode. The picture on the left is one of his: “a graph that essentially tells you the whole story in one simple, self-explanatory picture.” Yes indeed, social unrest is caused by higher food prices. ((Yes, caused; this is no mere correlation.)) I could leave it at that, along with a link to the paper from which I lifted the picture. But this is a podcast. I have to talk to people, and that includes Marc Bellemare.

“If you can tell your story with a graph or picture, do so,” says Marc Bellemare, my first guest in this episode. The picture on the left is one of his: “a graph that essentially tells you the whole story in one simple, self-explanatory picture.” Yes indeed, social unrest is caused by higher food prices. ((Yes, caused; this is no mere correlation.)) I could leave it at that, along with a link to the paper from which I lifted the picture. But this is a podcast. I have to talk to people, and that includes Marc Bellemare. In a world in which you can get pizza in Tokyo and sushi in Rome, diets have become truly global in reach. You could argue that this has made them more, not less, diverse. Where once rice dominated Asia, wheat, potatoes and corn have made huge inroads: increased diversity. On the other hand, places that used to enjoy their own, local staples – tef in Ethiopia, buckwheat in eastern Europe – have also come under the sway of the global behemoths, and so have lost diversity. Those are two conclusions of a massive data-mining exercise that has rightfully been getting a lot of coverage:

In a world in which you can get pizza in Tokyo and sushi in Rome, diets have become truly global in reach. You could argue that this has made them more, not less, diverse. Where once rice dominated Asia, wheat, potatoes and corn have made huge inroads: increased diversity. On the other hand, places that used to enjoy their own, local staples – tef in Ethiopia, buckwheat in eastern Europe – have also come under the sway of the global behemoths, and so have lost diversity. Those are two conclusions of a massive data-mining exercise that has rightfully been getting a lot of coverage: