Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:16 — 31.0MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

The history of pasta, ancient and modern, is littered with myths about the origins of manufacturing techniques, of cooking, of recipes, of names, of antecedents. Supporting most of these is a sort of truthiness whereby what matters most is not evidence or facts but – appropriately for us – gut feeling. Combine that with the echo chamber of the internet, and an idea can become true by virtue of repetition. So it is, by and large, for the idea that Arabs were responsible for inventing dried pasta and for introducing it to Sicily, from where it spread to the rest of the peninsula and beyond. You can find versions of this story almost everywhere you look for the history of dried pasta.

The history of pasta, ancient and modern, is littered with myths about the origins of manufacturing techniques, of cooking, of recipes, of names, of antecedents. Supporting most of these is a sort of truthiness whereby what matters most is not evidence or facts but – appropriately for us – gut feeling. Combine that with the echo chamber of the internet, and an idea can become true by virtue of repetition. So it is, by and large, for the idea that Arabs were responsible for inventing dried pasta and for introducing it to Sicily, from where it spread to the rest of the peninsula and beyond. You can find versions of this story almost everywhere you look for the history of dried pasta.

Anthony Buccini’s gut feeling, however, was that this story was not true. His expertise in historical linguistics and sociolinguistics tells him that the linguistic evidence for an Arab origin gets the whole story backwards; rather, one of the principal elements in the spread of dried pasta through Italy and beyond was the commercial expansion of Genoa. The stuff itself was being made in southern Italy, the Genoese took the word and the stuff to the north and to Catalonia, and it was the Catalonians who took them to the Maghreb and the Arabs.

So what did the Arabs do? They wrote it down in their cookbooks. And a bit more besides.

Notes

- The 2nd Perugia Food Conference Of Places and Tastes: Terroir, Locality, and the Negotiation of Gastro-cultural Boundaries took place from 5–8 June 2014. It was organized by the Food Studies Program of the Umbra Institute.

- World Pasta Day falls on 25th October. Enough time to prepare something special?

- Banner photograph taken by Su-Lin in Vancouver. Used with permission.

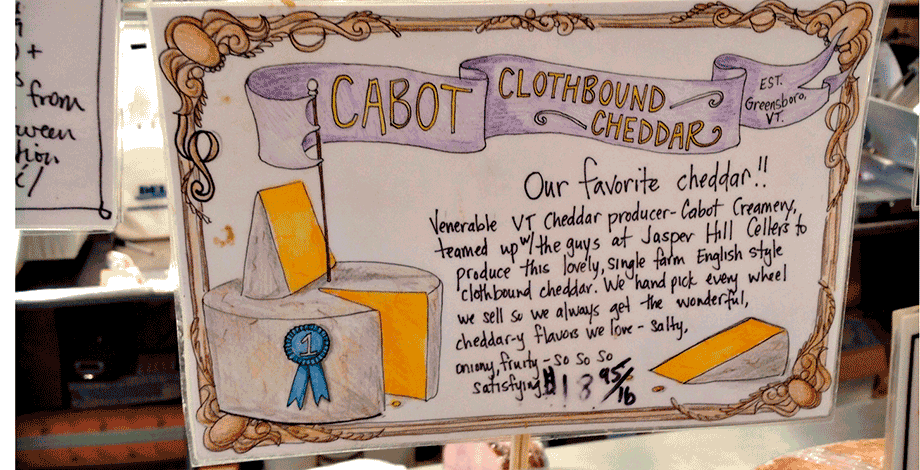

What do artisanal cheese and maple syrup have in common? In North America, and elsewhere too, they’re likely to bring to mind the state of Vermont, which produces more of both than anywhere else. They’re also the research focus of

What do artisanal cheese and maple syrup have in common? In North America, and elsewhere too, they’re likely to bring to mind the state of Vermont, which produces more of both than anywhere else. They’re also the research focus of

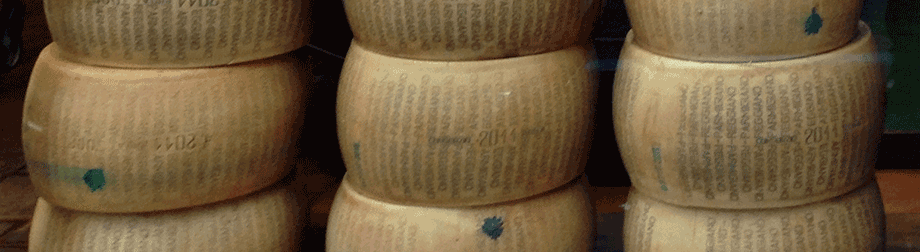

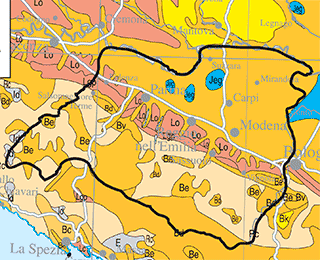

Great wheels of parmesan cheese, stamped all about with codes and official-looking markings, loudly shout that they are the real thing: Parmigiano-Reggiano DOP. They’re backed by a long list of rules and regulations that the producers must obey in order to qualify for the seal of approval, rules that were drawn up by the producers themselves to protect their product from cheaper interlopers. For parmesan, the rules specify how the milk is turned into cheese and how the cheese is matured. They specify geographic boundaries that enclose not only where the cows must live but also where most of their feed must originate. But they say nothing about the breed of cow, which you might think could affect the final product, one of many anomalies that Zachary Nowak, a food historian, raised during his presentation at the recent Perugia Food Conference on Terroir, which he helped to organise.

Great wheels of parmesan cheese, stamped all about with codes and official-looking markings, loudly shout that they are the real thing: Parmigiano-Reggiano DOP. They’re backed by a long list of rules and regulations that the producers must obey in order to qualify for the seal of approval, rules that were drawn up by the producers themselves to protect their product from cheaper interlopers. For parmesan, the rules specify how the milk is turned into cheese and how the cheese is matured. They specify geographic boundaries that enclose not only where the cows must live but also where most of their feed must originate. But they say nothing about the breed of cow, which you might think could affect the final product, one of many anomalies that Zachary Nowak, a food historian, raised during his presentation at the recent Perugia Food Conference on Terroir, which he helped to organise.

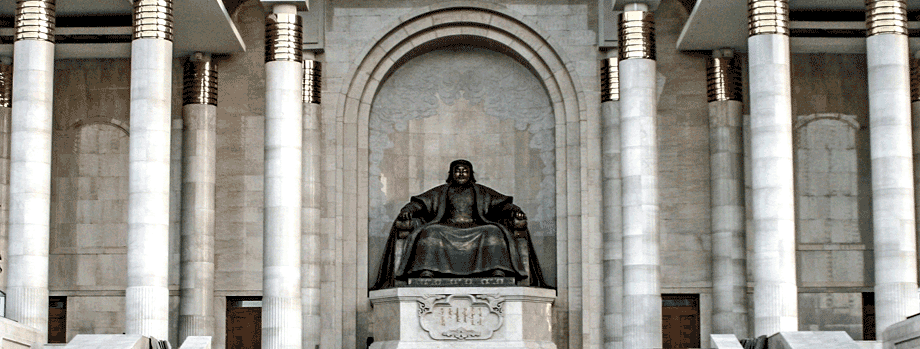

The growing popularity of “Mongolian” restaurants owes less to Mongolian food and more to, er, how shall we say, marketing. To whit:

The growing popularity of “Mongolian” restaurants owes less to Mongolian food and more to, er, how shall we say, marketing. To whit:

A Dutch food writer tries to discover the origins of pom, the national dish of Suriname. Is it Creole, based on the foodways of Africans enslaved to work the sugar plantations of Surinam? Or is it Jewish, brought to Suriname by Dutch Jews?

A Dutch food writer tries to discover the origins of pom, the national dish of Suriname. Is it Creole, based on the foodways of Africans enslaved to work the sugar plantations of Surinam? Or is it Jewish, brought to Suriname by Dutch Jews?