Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:34 — 23.5MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

The ancestry of modern maize has long been a puzzle. Unlike other domesticated grasses, there didn’t seem to be any wild species that looked like the modern cereal and from which farmers could have selected better versions. For a long time, botanists weren’t even sure which continent maize was from. That seemed to be settled with the discovery in lowland Mexico of teosinte, a wild and weedy relative of maize, and a lot of work to understand the genetic changes from teosinte to maize. The big problem was that the genetic work also seemed to contradict the story, by finding remnants of different types of teosinte. A new research paper sorts out the story, which is now more complicated, better understood, and offers some hope for future maize breeding.

The ancestry of modern maize has long been a puzzle. Unlike other domesticated grasses, there didn’t seem to be any wild species that looked like the modern cereal and from which farmers could have selected better versions. For a long time, botanists weren’t even sure which continent maize was from. That seemed to be settled with the discovery in lowland Mexico of teosinte, a wild and weedy relative of maize, and a lot of work to understand the genetic changes from teosinte to maize. The big problem was that the genetic work also seemed to contradict the story, by finding remnants of different types of teosinte. A new research paper sorts out the story, which is now more complicated, better understood, and offers some hope for future maize breeding.

Notes

- A summary of their research by Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra and his colleagues is available at Science.

- Here is the transcript.

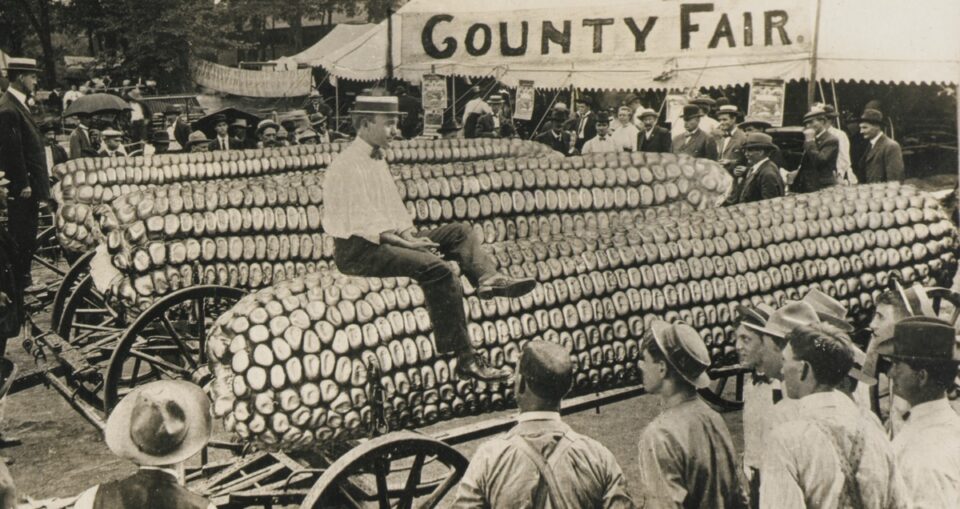

- Cover photo, sculpted head of a Mayan maize god, “represented as a vigorous youth with flowing hair likened to corn leaves”, he was considered to be the quintessence of beauty and refinement. Taken by me at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington DC. Banner photo by William H. Martin, who became very rich making these sorts of postcards.

Jeremy’s latest podcast is out, and it’s a doozie. Plus it saves me adding it to the next Brainfood, which is coming soon, don’t worry people.

Modern maize has long been a puzzle. Unlike other domesticated grasses, there didn’t seem to be any wild species that looked like the modern cereal and from which farmers could have selected better versions. For a long time, botanists weren’t even sure which continent maize was from. That seemed to be settled with the discovery in lowland Mexico of teosinte, a wild and weedy relative of maize. But there was a problem. A lot of the later genetic work to understand the transformation of teosinte into maize found remnants of different types of teosinte.

Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra and his colleagues have sorted out the story, which is now more complicated, better understood, and offers some hope for future maize breeding. Their paper was published last week in Science.