Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:59 — 17.0MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

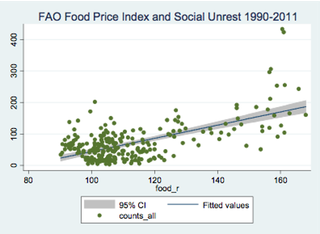

“If you can tell your story with a graph or picture, do so,” says Marc Bellemare, my first guest in this episode. The picture on the left is one of his: “a graph that essentially tells you the whole story in one simple, self-explanatory picture.” Yes indeed, social unrest is caused by higher food prices. ((Yes, caused; this is no mere correlation.)) I could leave it at that, along with a link to the paper from which I lifted the picture. But this is a podcast. I have to talk to people, and that includes Marc Bellemare.

“If you can tell your story with a graph or picture, do so,” says Marc Bellemare, my first guest in this episode. The picture on the left is one of his: “a graph that essentially tells you the whole story in one simple, self-explanatory picture.” Yes indeed, social unrest is caused by higher food prices. ((Yes, caused; this is no mere correlation.)) I could leave it at that, along with a link to the paper from which I lifted the picture. But this is a podcast. I have to talk to people, and that includes Marc Bellemare.

Bellemare’s paper is a global investigation that doesn’t even attempt to ask whether the relationship between food prices and social unrest holds for countries or smaller areas. My sense, though, is that the relationship is strongest in more authoritarian regimes. At least, that’s where we’ve seen most food riots of late. In this, however, it seems I am mistaken. Marc pointed me to Cullen Hendrix, who has studied the links between social unrest and political regimes. Placating the urban masses who eat food at the expense of rural people who produce it has always been a fraught proposition, perhaps even more so for democracies.

All of which raises the question that, I hope, keeps food policy wallahs and agricultural development experts awake at night. What’s so wrong with high prices anyway?

Notes

- Marc Bellemare’s blog post on his paper Rising Food Prices,

Food Price Volatility, and Social Unrest. He also examined some of the reactions to the paper. - “Even when presenting to the smartest people in the world, a picture is really worth a thousand words.” Find this and Marc’s other tips for conference and seminar presentations here.

- Cullen Hendrix’s website contains a copy of his paper International Food Prices, Regime Type, and Protest in the Developing World

- The sound montage at the beginning draws on various reports on Haiti, Egypt and Tunisia, all glued together by a splendid recording of a protest march.

- The banner photograph is adapted from an original by Martin Bureau/AFP/Getty Images.

https://media.blubrry.com/eatthispodcast/mange-tout.s3.amazonaws.com/2023/food-riots.mp3Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:01 — 28.5MB)Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

In her latest book English Food: A People’s History, Diane Purkiss offers just that, an entrancing survey of what and how the English ate, with due recognition that “‘the English’ are not a single entity” and that the past necessarily illuminates the present. Impossible to cover all that in a single episode, or even several, we set out to explore what happens when the vast bulk of the English do not have enough to eat. Food riots are a recurring feature of rural life in England, often the result of bad weather and always exacerbated by the action — or inaction — of the ruling classes. As Diane told me at the outset, “it might be faster to talk about what rebellions don’t have a food element”.

Notes

You can buy English Food: A People’s History online from an independent bookseller. It has just won the Guild of Food Writers award for Best Food Book of 2023.

Those uprisings:

Jack Cade’s Rebellion

Pilgrimage of Grace

Oxfordshire Rising

An episode from the vaults dealt with Food prices and social unrest in the context of the Arab Spring and more recent manifestations.

Swing letters from the British National Archive.

Here is the transcript.

Huffduff it

https://media.blubrry.com/eatthispodcast/mange-tout.s3.amazonaws.com/2023/egypt.mp3Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 29:02 — 26.9MB)Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Android | RSS | More

Jessica BarnesEgypt spends about 3% of its budget subsidising bread for about three-quarters of its population. Threats to that subsidy provoke massive civil unrest, helping to topple the regime in 2011. As a result, bread and wheat are fundamental to the government’s security and that of the people of Egypt. Wheat yields in Egypt are among the highest in Africa, but they are no match for the population, which is why Egypt is the biggest buyer of wheat on the global market. Even when government raises the price it will pay for local wheat, the farmers who grow it prefer to keep their harvest — for their own family food security — rather than sell it to promote the government’s security.

These are just some of the challenges Jessica Barnes brings to light in her new book, Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt.

Notes

Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt is published by Duke University Press.

Music by Ramy Essam.

You may be interested in an episode I did back in 2014: Food prices and social unrest

Transcript available here.

Cover photo by Hossam el-Hamalawy. Banner photo “courtesy Middle East Confidential”.

Huffduff it

The Global Chaos Map counts the deaths, including suicides, associated with “violent social unrest” linked to natural resources such as food, fuel and water. (See…

I’ve just finished listening to the Modernist BreadCrumbs Podcast. Some of the guests often had interesting things to say.

Flour power: why every revolution begins with a piece of bread in Prospect magazine also occupied me for a couple of minutes. I suppose it is a marker of the new grooviness of bread that the piece even exists, but does it have to peddle quite so many alternative facts?

No need to quote a pundit’s opinions when experts have actually studied food prices and social unrest.

What does “A bowl of gruel for one becomes dinner for six out of thin air.” actually mean?

The Big Mac index is not about “basic economic theory”; it is about the relative value of currencies, as The Economist helpfully tells us.

“[S]omething abysmal-sounding about mixing yesterday’s stale crusts with today’s fresh ’wheaten dow’” would not, I fancy, seem at all abysmal to the many bakers (mostly German in origin) who regularly add stale bread (altes) to their dough and make perfectly fine loaves that actually depend on the stale bread for their flavour.

It is not “a historical fact that Victorian millers’ habits of adding alum to the flour gave children rickets.”1 It is a historical fact that the great proto-epidemiologist John Snow hypothesised that this might be the case, but he offered nothing like convincing evidence, which yet might be obtained from the Victorian bones.

As an antidote to all my naysaying, treat yourself to Paul Levy’s Let them eat bread in the Times Literary Supplement, a lovely review of several books, including Modernist Bread, my point of departure for this little rant.

Was it even the millers, rather than the bakers? ↩

https://media.blubrry.com/eatthispodcast/op3.dev/e/mange-tout.s3.amazonaws.com/2016/ag-econ.mp3Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:02 — 23.0MB)Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More Speculators are responsible for…

[…] In space, nobody can hear you riot over food prices. […]