Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:10 — 23.3MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

Jonathan Bethony is one of the leading artisanal bakers in America, but he goes further than most, milling his own flour and baking everything with a hundred percent of the whole grain. He’s also going beyond wheat, incorporating other cereals such as millet and sorghum in the goodies Seylou is producing. I happened to be in Washington DC just a couple of weeks after his new bakery had opened, and despite all the work that goes into getting a new bakery up and running, Jonathan graciously agreed to sit down and chat.

Jonathan Bethony is one of the leading artisanal bakers in America, but he goes further than most, milling his own flour and baking everything with a hundred percent of the whole grain. He’s also going beyond wheat, incorporating other cereals such as millet and sorghum in the goodies Seylou is producing. I happened to be in Washington DC just a couple of weeks after his new bakery had opened, and despite all the work that goes into getting a new bakery up and running, Jonathan graciously agreed to sit down and chat.

Gluten

Jonathan impressed me with his live-and-let-live attitude to people who want to be gluten-free. I can only imagine how depressing it must be to have people shun the food you have dedicated your life to making. As he said, “I’m not a poison dealer”. But it did add to the motivation to pursue long fermentations and 100% whole grain flour, which does seem overall to make breads more digestible.

The Goods

Seylou is open from Wednesday to Sunday and was shut on the day I visited, so there was no chance to try anything. A couple of weeks later we went back for a coffee and something to eat, the proof of the pudding and all that. I was truly blown away. The whole grain croissant was an astonishing revelation. I simply could not imagine anything made of whole wheat could be so light and airy and yet so flavoursome. Same goes for the millet cookie. If I hadn’t been told, I’m sure I would never have guessed that it wasn’t wheat, and it had none of the self-righteous heftitude that “good-for-you” goods often have.

The bread I tried at my friend’s house. It was obviously not as light as a croissant, nor would I have wanted it to be, but it was moist and chewy and again incredibly tasty. Also, filling. A single slice mid-morning took me well into the afternoon.

As a bread baker myself, perhaps the secret is in the difference between harder and softer wheats, as Jonathan said, and how softer wheats result in bigger flecks of bran, which can make getting a good open crumb more difficult. In Italy I’ll often demonstrate the presence of bran in wholewheat flour by sifting a small sample, leaving the bran behind. When I tried that recently with some high-quality US-milled wholewheat, there was almost no bran left behind. It had been truly pulverised. I’m still a ways away from buying a home mill, but now I’m wondering; if I sifted my Italian flour for a bake and blitzed the bran in a food processor, would that make for a lighter loaf?

Varieties

You might imagine that an artisanal baker who talks about respect for the farmers and all they do for the land and for their grains would be using only ancient heirloom varieties, handed down from one generation to the next and tightly adapted to the farms on which they grow. You’ld be right, but only partly so. One variety Jonathan bakes with is probably at least 200 years old. Another was born yesterday.

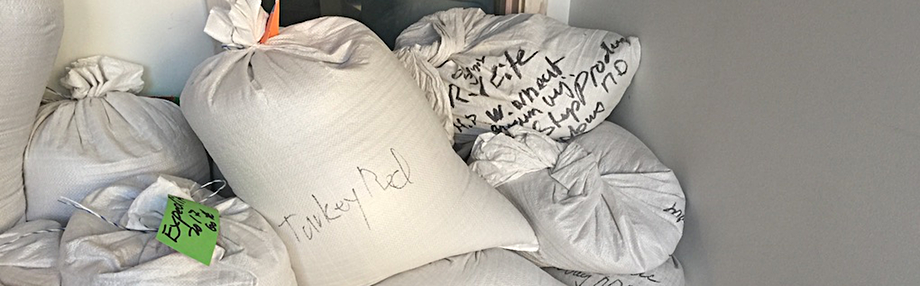

Turkey Red is a really old variety with a murky origin story, even after it reached the US. Some say that it was first planted in 1874 in Kansas by immigrant German-Russian farmers fleeing conscription in the Crimea, who brought it with them in their suitcases, trunks and special chests. Others credit a single farmer – Bernhard Warkentin – a German-speaking Mennonite from what is now Ukraine, who arrived in Kansas in the early 1870s scouting for good places to grow wheat. His father was a miller who had introduced Turkey Red to the area around Odessa in the Crimea, though nobody knows its history before that. While the early immigrants may have grown a little Turkey Red on their arrival, in 1885 and again in 1900 Warkentin was charged with importing “several thousand bushels of new seed” of Turkey Red from Crimea.

The variety became one of the foundations of the breadbasket states of the USA and a vital part of the economy of Kansas, but starting in the 1940s new, high-yielding varieties pushed it out to just a few small fields, the province of hobby farmers. In 2009 Slow Food USA added it to the Ark of Taste and that heralded something of a rennaissance, with Turkey Red finding new places to grow, close enough to Washington DC for Jonathan to consider it local.

Appalachian White sounds as it if could have much the same back story, but it’s ancestry is very different, and much better known. Its parents are KS2016-U2 and Lakin, themselves both relatively modern Kansas varieties, crossed deliberately to create a hard white winter wheat that would thrive in the eastern United States, where the climate is much damper than on the plains. The USDA released it to farmers in 2010 and it is now being grown quite widely in North Carolina and Virginia. Not as glamorous as Turkey Red, but also much more useful to farmers, millers and bakers on the east coast, especially those who want organic, local flour, which is exactly what the USDA breeders had in mind.

More

It was an article on NPR’s The Salt that first brought Seylou Bakery to my attention, followed after a bit of digging by a slightly earlier piece in The Washington Post. And here are three links to pieces in which Jonathan (and others) share what they know about baking good bread:

- Whidbey Bread: Whole Grains for the Home Baker, a Bread Lab workshop

- Could This Baker Solve the Gluten Mystery?

- 12 Tips from The Bread Lab, Where Baking is Like Playing an Instrument

As for the bakery’s back story, the Seylou website has that.

Has it really been almost five years since I visited? Time flies when you’re having fun. I listened again to Jonathan and it is no great surprise that Seylou has gone from strength to strength. eatthispodcast.com/bread-as-it-ou…

@seyloubakery Has it really been almost five years since I visited? Time flies when you’re having fun. I listened again to Jonathan and it is no great surprise that Seylou has gone from strength to strength. https://www.eatthispodcast.com/bread-as-it-ought-to-be/

enjoyed the excellent @eatpodcast on bread 🍞eatthispodcast.com/bread-as-it-ou… wondering what the nearest equivalents to @seyloubakery are the UK?

Pretty cool podcast. When I talk about other bakeries who are “doing it like we do” I always mention Seylou now. eatthispodcast.com/bread-as-it-ou…

One of the things that really struck me in this conversation was the produce influencing the product. Jonathan Bethony talks about the different forms of grain and finding the right type of bread to bake with it. Rather than depending on adding sugars, alcohol and herbs, the Bethany explains that the grains provide all the flavour required. This reminds me of the notion of the assemblage and learning that occurs between the different parts.

Bread as it ought to be: Seylou Bakery in Washington DC by Jeremy Cherfas from Eat This Podcast

If possible, click to play, otherwise your browser may be unable to play this audio file.

And almost as if to prove my point after writing about Modernist BreadCrumbs the other day, Jeremy’s latest episode is a stunning example of love and care in a podcast dedicated to food. I’m really so pleased that he can take a holiday, have so much fun with bread, and simultaneously turn it into something like this.

Even the title reads as if he were trying to out-do the entirety of eight episodes of Modernist BreadCrumbs in one short interview. I think he’s succeeded handily.

There’s so much great to unpack here, and simultaneously I wish there was more. I found myself wishing he’d had time to travel to some of the farms and done a whole series. With any luck he actually has–I wouldn’t put it past him–and we’ll be delighted in a week or two when they’re released.

Syndicated copies to:

Author: Chris Aldrich

I’m a biomedical and electrical engineer with interests in information theory, complexity, evolution, genetics, signal processing, theoretical mathematics, and big history.

I’m also a talent manager-producer-publisher in the entertainment industry with expertise in representation, distribution, finance, production, content delivery, and new media.

View all posts by Chris Aldrich

Inspired by Jeremy Cherfas and his #podcast episode Bread as it ought to be.I am making my first bread in a few years.

500g of white flour (only flour I could find).

2 teaspoons of salt.

1 teaspoon of sugar.

splash of olive oil.

warm water.

7g of yeast.

Jeremy’s advice is to use half the yeast and let it rest for twice as long.

I’m not brave enough to use half the yeast on my first attempt today , but will leave it all day to rise.

Update : Disappointingly the loaf came out rather flat , like a thick buscuit , I think I left it too long before kneeding and not long enough afterwards.

Also need to cook in a very hot oven.

#homemade #bread

Jonathan Bethony, who runs Seylou Bakery in Washington DC, mills his own wheat and uses 100% of the grain. Talking to him for Eat This Podcast I learned about the difference in bran between softer European wheats and harder North American wheats. My wholemeal, from softer wheats, has larger flecks of bran that cut through the gluten network so the bread doesn’t rise as much. Having learned more of the details, I decided to give my brown flour a really long soak before making the dough.

This soaking period, without any leavening, is usually called an autolyse. Before, I’ve generally done a 30 minute autolyse, maybe an hour. Then lately I upped it to overnight, although that was for all the flour. For an experiment, I decided yesterday to soak only the wholemeal. I hoped that a long soak with more available water (not absorbed by the white flour) would soften the larger flecks of bran even more, so the dough structure would survive better. Also, hearing that Jonathan pushes hydration to 100 and even 110 percent, I thought that I could usefully push mine to 80% (from about 70% most of the time).

So, at the same time as I started the second build of the wholemeal leaven, I put the rest of the wholemeal to soak in all of the water, 300g of flour in 600g of water (200% hydration). A soupy mess. Eight hours later I added the leaven (350g at 75%), the strong white flour (500g) and the salt (17g). After mixing by hand to incorporate and distribute everything I did a set of folds at roughly 30, 60 and 120 minutes. After three hours of bulk fermentation I pre-shaped the loaves as gently as I could, gave them a bench rest of 30 minutes and then put the shaped loaves into the fridge for an overnight rise.

Slashed and baked from cold in a Dutch oven at 235°C for 26 minutes, before removing the lid and giving another 26 minutes at a slightly lower temperature.

The rise was great, with good oven spring. The texture was fabulous, with a crisp crust and a soft, light crumb. The structure was open, without any giant holes, and that’s the way I like it, uh huh.

Tasted pretty good too. I could be mistaken but I think the nuttiness of the grain is more pronounced and perhaps the long fermentation also brings out more of the natural sweetness. Next time I might even try pushing the hydration to 85%

Latest episode — with @seyloubakery — ready for consumption

eatthispodcast.com/bread-as-it-ou…

❤️

Seylou shared a post.

“It used to be you worked to make white flour. Now you work to make brown bread.”–great interview Jeremy, thanks! RT @eatpodcast: Latest episode — with @seyloubakery — ready for consumption ow.ly/uXAp30hXEHi

Do it! You won’t be disappointed.

Latest episode of Eat This Podcast is up now. Bread as it ought to be.

❤️

I have been trying to get there. Sounds great.

Latest episode — with @seyloubakery — ready for consumption

eatthispodcast.com/bread-as-it-ou…