Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:01 — 17.9MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

In the past year or so there has been a slew of high-level meetings pointing to antibiotic resistance as a growing threat to human well-being. But then, resistance was always an inevitable, Darwinian consequence of antibiotic use. Well before penicillin was widely available, Ernst Chain, who went on to win a Nobel Prize for his work on penicillin, noted that some bacteria were capable of neutralising the antibiotic.

In the past year or so there has been a slew of high-level meetings pointing to antibiotic resistance as a growing threat to human well-being. But then, resistance was always an inevitable, Darwinian consequence of antibiotic use. Well before penicillin was widely available, Ernst Chain, who went on to win a Nobel Prize for his work on penicillin, noted that some bacteria were capable of neutralising the antibiotic.

What is new about the recent pronouncements and decisions is that the use of antibiotics in agriculture is being recognised, somewhat belatedly, as a major source of resistance. Antibiotic manufacturers and the animal health industry have, since the start, done everything they can to deny that. Indeed, the history of efforts to regulate the use of antibiotics in agriculture reveals a pretty sordid approach to public health.

But while it can be hard to prove the connection between agriculture and a specific case of antibiotic resistance, a look at hundreds of recent academic studies showed that almost three quarters of them did demonstrate a conclusive link.

Antibiotic resistance – whether it originates with agriculture or inappropriate medical use – takes us back almost 100 years, when infectious diseases we now consider trivial could, and did, kill. It reduces the effectiveness of other procedures too, such as surgery and chemotherapy, by making it more likely that a subsequent infection will wreck the patient’s prospects. So it imposes huge costs on society as a whole.

Maybe society as a whole needs to tackle the problem. The Oxford Martin School, which supports a portfolio of highly interdisciplinary research groups at Oxford University, has a Programme on Collective Responsibility for Infectious Disease. They recently published a paper proposing a tax on animal products produced with antibiotics. Could that possibly work?

Notes

- The paper by Alberto Giubilini and his colleagues is Taxing Meat: Taking Responsibility for One’s Contribution to Antibiotic Resistance. He also wrote an article explaining why we should tax meat that contains antibiotics.

- Claas Kirchhelle’s paper on the history of antibiotic regulation in Britain will be published in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine. His prize-winning D.Phil thesis Pyrrhic Progress – Antibiotics and Western Food Production (1949–2013) will be published by Rutgers University Press.

- Reducing antimicrobial use in food animals, published in Science after I had talked to Alberto and Claas, has some interesting things to say about a tax on antibiotics and other ways to tackle antibiotic resistance.

- The UK government’s Review on Antimicrobial Resistance is a valuable source of information.

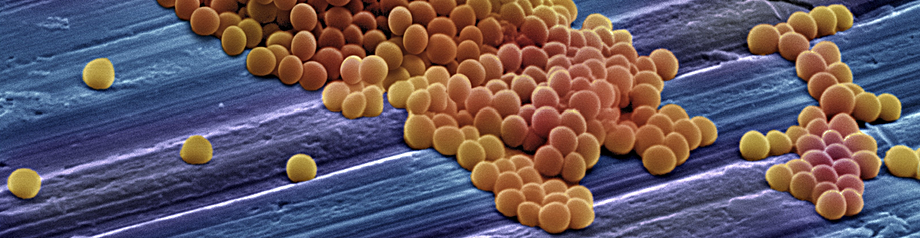

- Pig pill image from the National Academy of Medicine. Banner image of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from the Wellcome Trust.

[…] https://www.eatthispodcast.com/antibiotics-and-agriculture/ […]

The introduction to a new report about livestock antibiotic resistance in Science states unequivocally that “There is a clear increase in the number of resistant bacterial strains occurring in chickens and pigs.” It also, somewhat disingenuously in my view, says “It is unclear what the increase in demand for antibiotics means for the occurrence of drug resistance in animals and risk to humans.”

It has been clear almost since the first deployment of antibiotics that resistance to them evolves, and that the more antibiotics are used, the more resistance we can expect. I well remember, back in 1982, Stuart Levy warning me and anyone else who would listen that the world was already a dilute solution of Tetracycline. Levy died earlier this month, and yesterday’s Washington Post carried a very good obituary. It gives the background to his ground-breaking research, published in 1976, that the routine use of antibiotics on a chicken farm resulted in resistant bacteria in people who lived nearby. I can imagine what he might say to this conclusion from this latest report:

Little-known fact: Levy’s original study was funded by the Animal Health Institute, who hoped his results would support their view that routine antibiotics were useful and effective with no downside risks. As the Post’s obituary notes:

Amen.

Eat This Podcast’s episode Antibiotics and agriculture examined this history of antibiotics on farms and one possible solution.

@khaosanlao Taxation is unlikely to be part of the mix #AMRhub will offer, but there’s a good case to be made elsewhere. Listen here: https://www.eatthispodcast.com/antibiotics-and-agriculture/

Reading time: 6 min 4 secTakeaway: Grass-fed beef is supposedly better than “regular” beef. But why? This post lays out the definition(s) of grass-fed beef, potential benefits and where to find it if you decide it’s what you want.

I really struggled with this post. I concluded the best thing is to share what I’ve learned in the past couple of years about grass-fed beef. There’s loads more to learn, but let’s do what my dad always recommended for public discourse – KISS! (Keep it simple, stupid.)

P.S. Notice all the qualifiers I’m using in this post–they are intentional! Where a cow is raised and slaughtered, the breed of cow, the amount and type of forage available, etc., affect the nutritional profile, flavor and carbon footprint of beef production. These create quite a few variables in the equation when determining which is “better”.

What’s your beef?

Google Satellite Images. October 9, 2017. On the left are feedlots in Dalhardt, Texas, showing waste lagoons and hundreds of cows. On the right is an image that contains my uncle’s place, where he keeps about a dozen cows on pasture. Image scale is the same.

You’re a responsible person. You want to eat well, but not spend too much. And maybe you eat beef irregularly, but when you do, you want it to be delicious, good for you, and good for the planet. Are these things even possible? Are they mutually exclusive? And, more practically, which hamburger meat should you buy-the cheaper “conventional” one or one labelled “grass-fed”?

The short answer is, “It depends.” Which one you should buy depends on what you value most; this post endeavors to help you decide, based on facts.

Grass-fed vs. “regular” beef characteristics

Before we get underway, some definitions to get us on common ground.

Grass-fed or Pastured

Did you see my post on labels? Essentially, “grass-fed” or “pastured” means little, unless it’s backed up by something like American Grass-fed Association or you’re talking straight to the farmer who can tell you what they mean by grass-fed. About 80% of beef in the US, by weight, comes from when cows graze on grass. Most cows, whether strictly grass-fed or finished in a feedlot with grain, spent the first 6-9 months or so of their lives grazing in a pasture.

American Grassfed Association

Conventional beef

“Regular” beef, that is, beef not labelled as grass-fed, grass-finished or pastured generally spends about two-thirds of its life in pastures.

100% Grass-fed/Pastured, Grass-finished

These labels are trying to let you know that their cows have only eaten grass. How strict this is will vary by the producer.

Potential Benefits

Some of the first information I read about grass-fed beef was how healthy it is compared to regular beef. Like many health claims, that is not wholly true. I also liked the idea of cows living a life closer to their nature and without needing grain to be produced to boost their weight, a practice that could increase the environmental footprint of beef production.

Health and Nutrition Claims (compared to grain-finished beef)

More conjugated linoleic acid (CLA)

More Vitamin A

More omega-6 fatty acids give it a better ration of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids

Lower fat content

And now for the qualifiers…

Put simply, compared to grain-finished beef, these things are all true. However, most are only marginally better in grain-fed beef.

CLA – This one is legit, there is significantly more CLA in beef than other sources. That said, I can’t find conclusive evidence that CLA is good for us. Also, studies note that you can get increased amounts of CLA from just increasing the fat content of the beef you eat, rather than switching to grass-fed. If you find better data that CLA is conclusively good, let me know in the comments!

Vitamin A – The National Institute of Health (NIH) shows that a serving of beef liver has 444 percent of our recommended daily value (RDV). For comparison, one sweet potato has 561 percent of the RDV.

Omega-6:Omega-3 – A great blog-post on Grass Based Health shows the various amounts of measured ratios in grass versus grain fed beef. They range from as low as 1.44 in grass and 13.6 in grain-fed beef (a lower ratio is better). So, yeah, there is a better ratio. That’s great. BUT…compared to other sources, like fatty fish, the overall amount of omega 3 is abysmally low (tuna has about 30 times more omega 3).

Lower fat content – Roughly half as much fat, per four studies cited here-see Table 2. That sounds impressive, but it’s only about 2-4 grams difference in a 100 gram serving. (The recommended daily allowance of total fat based on a 2000 calorie diet is 65 grams of fat, so 4 grams is only 6% of the RDA.)

Environment

Lower carbon footprint.

Improved carbon-carrying capacity of grasslands. (This means there are a greater total number and higher activity of plants and micro-organisms that are helping take more carbon from the atmosphere.)

Both of these should lead to fewer greenhouse gasses; however, like most things related to life-cycle analysis, it depends on a number of variables.

Cattle production produces greenhouse gasses at a number of points in the value chain, including:

When they belch. Because they’re ruminants, this means their food is fermenting in their stomachs. Different foods lead to different amounts of gas.

When they poop. Ditto to above.

When they are fed supplemental food, whether it’s grain, grass or otherwise. The carbon involved in producing the food adds to the footprint of the cow. Grains typically require more nitrogen based fertilizer than grass production, which means grains have a higher carbon footprint. You also have to account for drying and transportation to the feeding area for most grains.

Variables include:

The breed, as some breeds are better at converting forage into calories, that is, they turn grass into meat quicker and with fewer methane emissions.

The food stock. Grains generally cause cows to emit more methane than eating grass.

Time to slaughter. More food, even in the pasture, can lead to more methane emissions. Since grass-fed cows may be on pasture up to a year longer, the reduction in emissions from eating grasses can be offset by the total amount of food they eat over their lifetime and the methane produced thereby. Therefore, grass-fed and grain-fed cows may have the same amount of lifetime gas emissions.

Papers I’ve found (here and here) indicate conventional beef has a lower footprint.

Final thoughts

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention animal welfare. This is more qualitative and subjective. Even if you’re not a vegetarian or vegan, you may be concerned about animal welfare. It’s a constant internal struggle of fact vs. feeling for me–I can read and cite the facts, but when it comes down to it, it’s my heart that ultimately decides. I prefer to know my food lived an idyllic life, and I’m willing to pay more and/or eat less of it. Just as foregoing meat is a personal choice, this is as well. I prefer farms that have been Animal Welfare Approved. Their list of criteria is robust, as is their certification system.

To be transparent with you, I would have enjoyed demonstrating that research indicates grass-fed beef is better for us and the planet. Scientifically-speaking, telling you such would be going against the facts we have today. Perhaps next time I’ll look at papers following antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance and find something there. (Coincidentally, there was a podcast from Eat This all about antibiotics. See here and here.)

I know we didn’t make any sweeping conclusions here; however, I hope you feel like you’ve gained a bit of knowledge to help you decide what’s aligns with your values.

Where to find grass-fed (and finished) beef in the Piedmont Triad

Firsthand Foods – Find them in Deep Roots Market in downtown Greensboro

Summerfield Farms

At the Greensboro Farmers Curb Market:

Six Gunn FarmMeadows Family Farm

Rothchild Angus Farm

Share this:

Twitter

Facebook

Google

LinkedIn

Pinterest

Email

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related

Love your podcasts! I met you at SeedSavers Exchange at a Campout you were a speaker(you lived in Italy then). We had a lovely conversation over some local beer. I have enjoyed following you. My group is SeedSavers-KC.org. I shared on our FB group. Great podcast on antibiotics-love the taxation idea!

Thanks KC; glad you are enjoying it all.

Antibiotics and agriculture by Jeremy Cherfas from Eat This Podcast

If possible, click to play, otherwise your browser may be unable to play this audio file.

Here’s another great example of a negative externality. Too often capitalism brushes over these and creates a larger longer term cost by not taking these into account. It’s almost assuredly the case that taxing the use of these types of antibiotics across the broadest base of users (eaters) (thereby minimizing the overall marginal cost), would help to minimize the use of these or at least we’d have the funding for improving the base issue in the future. In some sense, the additional cost of eating organic meat is similar to this type of “tax”, but the money is allocated in a different way.

Not covered here are some of the economic problems of developing future antibiotics when our current ones have ceased to function as the result of increased resistance over time. This additional problem is an even bigger worry for the longer term. In some sense, it’s all akin to the cost of smoking and second hand smoke–the present day marginal cost to the smoker of cigarettes and taxes is idiotically low in comparison to the massive future cost of their overall health as well as that of the society surrounding them. Better to put that cost upfront for those who really prefer to smoke so that the actual externalities are taken into account from the start.

This excellent story reminds me of a great series of stories that PBS NewsHour did on the general topic earlier this year.

If you love this podcast as much as I do, do consider supporting it on Patreon.

Syndicated copies to:

Related

Author: Chris Aldrich

I’m a biomedical and electrical engineer with interests in information theory, complexity, evolution, genetics, signal processing, theoretical mathematics, and big history.

I’m also a talent manager-producer-publisher in the entertainment industry with expertise in representation, distribution, finance, production, content delivery, and new media.

View all posts by Chris Aldrich

New podcast featuring @AlbertGiubilini & Claas Kirchhelle on taxing meat with antiobiotics and current use of agricultural antibiotics.