Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:04 — 23.5MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

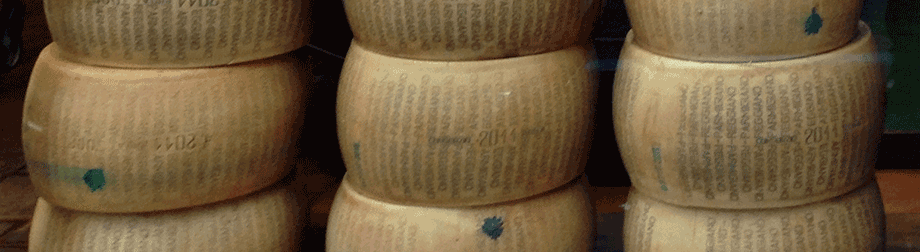

Great wheels of parmesan cheese, stamped all about with codes and official-looking markings, loudly shout that they are the real thing: Parmigiano-Reggiano DOP. They’re backed by a long list of rules and regulations that the producers must obey in order to qualify for the seal of approval, rules that were drawn up by the producers themselves to protect their product from cheaper interlopers. For parmesan, the rules specify how the milk is turned into cheese and how the cheese is matured. They specify geographic boundaries that enclose not only where the cows must live but also where most of their feed must originate. But they say nothing about the breed of cow, which you might think could affect the final product, one of many anomalies that Zachary Nowak, a food historian, raised during his presentation at the recent Perugia Food Conference on Terroir, which he helped to organise.

Great wheels of parmesan cheese, stamped all about with codes and official-looking markings, loudly shout that they are the real thing: Parmigiano-Reggiano DOP. They’re backed by a long list of rules and regulations that the producers must obey in order to qualify for the seal of approval, rules that were drawn up by the producers themselves to protect their product from cheaper interlopers. For parmesan, the rules specify how the milk is turned into cheese and how the cheese is matured. They specify geographic boundaries that enclose not only where the cows must live but also where most of their feed must originate. But they say nothing about the breed of cow, which you might think could affect the final product, one of many anomalies that Zachary Nowak, a food historian, raised during his presentation at the recent Perugia Food Conference on Terroir, which he helped to organise.

In the end the whole question of certification is about marketing, prompted originally by increasingly lengthy supply chains that distanced consumers from producers. One problem, as Zach pointed out, is that in coming up with the rules to protect their product, the producers necessarily take a snapshot of the product as it is then, ignoring both its history and future evolution. They seek to give the impression that this is how it has always been done, since time immemorial, while at the same time conveniently forgetting aspects of the past, like the black wax or soot that once enclosed parmesan cheese, or the saffron that coloured it, or the diverse diet that sustained the local breed of cattle. One aspect of those forgettings that brought me up short was the mezzadria, a system of sharecropping that survived well into the 1960s. Zach has written about it on his website; some of the memories of a celebrated Perugian greengrocer offer a good starting point.

Will some enterprising cheesemaker take up the challenge of producing a cheese as good as Parmigiano-Reggiano DOP somewhere else? No idea, but if anyone does, it’ll probably be a cheesemaker in Vermont, subject of the next show.

Notes

- The 2nd Perugia Food Conference Of Places and Tastes: Terroir, Locality, and the Negotiation of Gastro-cultural Boundaries took place from 5–8 June 2014. It was organized by the Food Studies Program of the Umbra Institute.

- Wikipedia has masses of information about Geographical indications and traditional specialities in the European Union and, of course, Parmigiano-Reggiano which may, or may not, be parmesan.

- Official site of the Consorzio del Parmigiano-Reggiano.

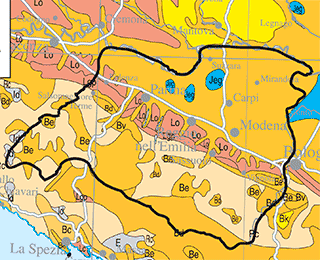

- Thanks to Zachary Nowak for his map of the soils of the Parmigiano-Reggiano DOP.

- 2019-05-05 Updated with link to Internet Archive.

So many ways to parse “100% grated parmesan cheese” none of which cares about where the cheese comes from. Listen to eatthispodcast.com/what-makes-par…

So many ways to parse “100% grated parmesan cheese” none of which cares about where the cheese comes from. Listen to eatthispodcast.com/what-makes-par…

[…] A podcast on what it takes to make parmigiano reggiano. […]

I have attended tastings of both Parmigiano-Reggiano DOP and Grana Padano DOP, and found them very similar in taste and texture. Many people refer to Grana as parmesan cheese. Both regions produce some outstanding cheeses, and often Grana is less expensive than a Parmigiano of the same quality.